Formula 1 News: 2024 Mexico City GP Preview

After the USGP in Austin, Texas last weekend, the F1 teams headed south from the United States to Mexico for the Mexico City Grand Prix.

The venue, located in a park in the eastern districts of Mexico City’s large sprawl, first played host to Formula 1 in 1963, under the name of the Autódromo Magdalena Mixhuca. It was subsequently renamed in honor of Mexico’s famous racing brothers, Pedro and Ricardo Rodriguez. The Autódromo Hermanos Rodríguez is in its third stint on Formula 1’s world championship calendar, having made a well-received comeback in 2015.

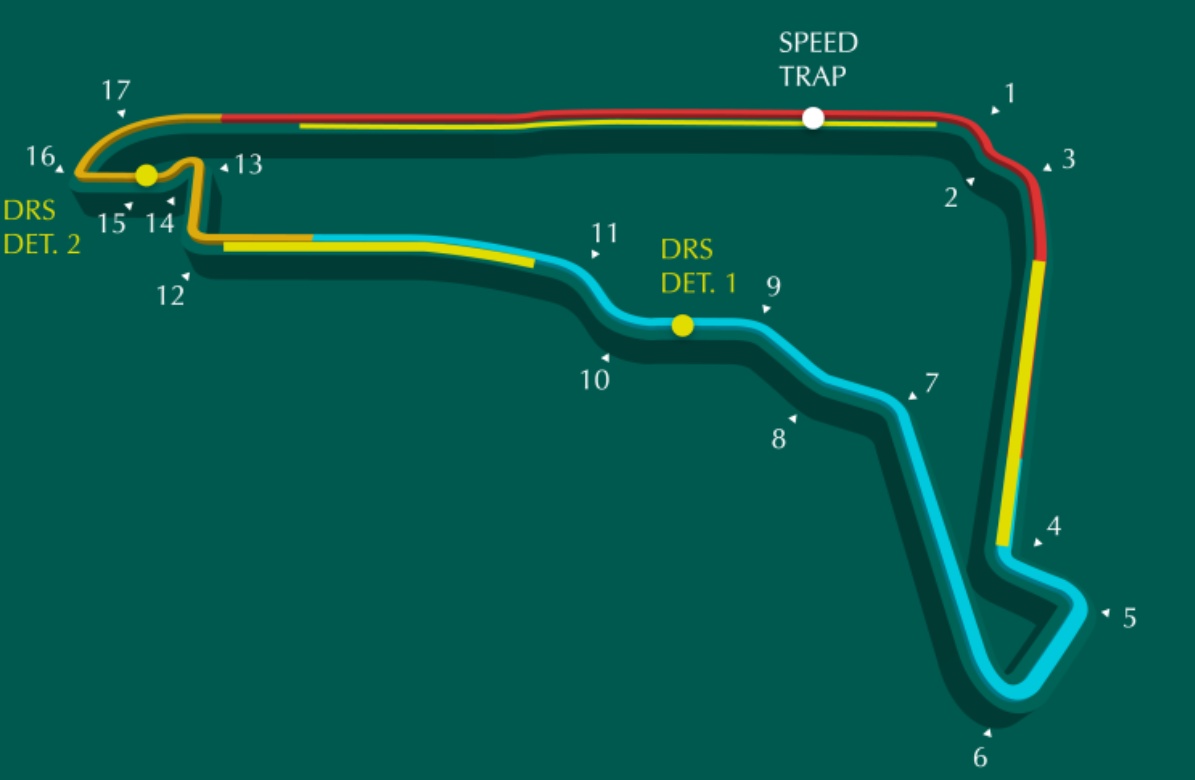

The Autódromo Hermanos Rodriguez features distinct sessions across its 4.3km layout. The first sector includes a couple of lengthy straights, divided by a medium-speed right-left-right chicane, before a slow-speed complex opens out into high-speed esses through the middle portion of the lap. The final sector is dominated by the Foro Sol stadium, the 30,000-seater structure, with a twisty slow-speed section passing beneath the arena. But the biggest aspect of the Autódromo Hermanos Rodríguez is not something visible to the naked eye: the altitude. Mexico City rests 2,260 meters above sea level, making it by far the highest venue on the Formula 1 calendar.

As a consequence, straight-line speed is among the highest of the season due to the low drag though this negates the impact of DRS, which can hinder overtaking, an element accentuated by the difficulty of cooling Formula 1 cars in the thinner air. There is also less downforce available at high altitude, which means drivers have to contend with more sliding through the high-speed esses, while ensuring brakes and tires are in the optimum window is also harder because of the altitude’s impact on surface temperatures and cooling ability.

The Autodromo Hermanos Rodriguez, named after Mexico’s famous racing brothers Pedro and Ricardo, is located in the eastern suburbs of Mexico City’s sprawling metropolis.

It is one of the most vibrant events on Formula 1’s calendar, with a frenzied crowd occupying the Foro Sol stadium – through which the circuit passes – most notable when home hero Sergio ‘Checo’ Perez drives through. Mexico City is a colorful and captivating event, enhanced by the history and culture present in the capital, and heightened further by the Dia de los Muertos, the world-famous festival which typically coincides with the grand prix’s date.

What to look for

- Race interruptions: There’s little margin for error at Autódromo Hermanos Rodríguez, which means race interruptions are frequent: in the past five races there has been one Safety Car and six Virtual Safety Cars. In 2022, there were two DNFs in the race – with the lower air density making engine cooling more difficult.

- Overtaking: Despite having a long straight and three DRS zones, overtaking is more difficult than at many other circuits; Mexico City’s high altitude means lower air density, which reduces the slipstream and DRS effect.

- Strategy: Pirelli have allocated C3, C4 and C5 tires for this year’s race – one step softer than in 2022 – which could change the optimal strategy for what has historically been a one-stop race. A new version of the C4 will be tested by all teams during free practice in preparation for 2024.

- Antonelli: Andrea Kimi Antonelli will drive for Mercedes in the opening F1 practice session at this weekend’s Mexico City Grand Prix. Antonelli will drive in Lewis Hamilton’s Mercedes in the first 60 minutes of practice at the Autodromo Hermanos Rodriguez on Friday. Antonelli replaced George Russell in FP1 at Monza, but crashed heavily in the Parabolica and embarrassed himself. The 18-year-old Italian will get another opportunity to drive the W15 as he prepares to make his F1 debut next year.

It’s a challenge – both physically and technically with the car – cooling is an issue. You don’t have as much downforce, you run a lot of wing on the car, and it’s very low density in the air, so you actually have about the same amount of downforce as you have in Monza. That’s why we’ve seen some of the highest top speeds from Formula 1 cars there. It’s tough physically and in the past, drivers have had Altitude Sickness from being so high up.

Fact File: Mexico City Grand Prix

- The Autódromo Hermanos Rodríguez is the third-shortest circuit on the 2023 F1 calendar, behind only Zandvoort and Monaco.

- It does, however, have the longest run from pole position to the first braking zone at 811 meters.

- Mexico City sits at over 2,200 meters altitude, which affects the car in a number of different ways.

- Because of that high altitude and therefore low air density, the air is incredibly thin.

- The ambient pressure is by far the lowest of the season at 782mb.

- The oxygen levels are therefore 78% of what they are at sea level. This has a big impact on the aerodynamics and the Power Unit.

- The nature of the circuit means drivers make only 35 gear changes per lap, the lowest number of the season.

- The ambient pressure is the lowest of the season by far. At 780mb, the oxygen levels are 78% of what they are at sea level, and this has a big impact on different areas of a Formula One car, such as Power Unit performance and downforce.

- Because you can run a Monaco wing level but experience Monza levels of downforce, top speeds in Mexico are some of the highest of the season, where the cars can achieve 346 km/h (or more with a tow). Only Vegas is higher.

- The Autódromo Hermanos Rodríguez still largely follows the original outline of the circuit, which was first developed in 1959.

- The main difference is the former, more fearsome version of the Peraltada corner is now bisected.

- The first championship Grand Prix race took place at the circuit in 1963, before disappearing from the calendar after 1970.

- The second F1 stint at the circuit came between 1989 and 1992, before the championship returned in 2015 with Nico Rosberg victorious for Mercedes.

Unlocking the lap

Turn One may appear no different to many similar corners on the calendar, but it is a challenge. The approach-speed is one of the highest on the calendar, which makes finding a braking point tricky, and the lack of downforce due to the altitude only adds to that. Additionally, the exit needs to be compromised heavily for the chicane that immediately follows.

The Esses – Turns Seven through to 11 – is where the cars will usually rely the most on the downforce. With aero grip drastically reduced – despite teams running very high levels of wing – it makes this sequence of fast bends all the trickier. Turn 10 in particular is tough and it is easy to lose stability through this corner.

Concluding the lap are Turns 16 and 17. The sharper of the two right-handers – named after Nigel Mansell – is crucial to the lap, while also setting up the next one for the very long pit straight that follows. The last corner, while still called Peraltada, is a shadow of its former self but requires a tricky balancing act on the throttle to maximize acceleration on to the main straight.

Into thin air

It’s not something you immediately feel. Altitude sneaks up on you, quietly, invisibly, just like the oxygen that your body craves, and of which it is, partially, deprived. You can go around your day, not feeling a difference, but the change is there: working its way into your lungs, forcing your heart to work a little bit harder. Go for a run, a gym session or a game of tennis, and that’s where it hits you: your body doesn’t respond how it used to, it wants more energy, more fuel, more air.

Ever since sports became science, the effects of high altitude have been studied, analyzed, exploited for performance. From the sprinting world records at the 1968 Summer Olympics to the effect on endurance for those training in the highlands of Kenya (or, for those more inclined to local pursuits, St. Moritz), exercise and competition at altitudes have forged an indissoluble bond with sport.

The rarefied atmosphere affects in particular ways anything that sucks in air, uses it as part of the engine power development, and eventually moves through it as quickly as it possibly can – effectively, anything that a Formula One car does. Just like any athlete, cars struggle a bit more at higher altitudes: cooling is reduced; power output stunted; and downforce much reduced as there’s not as much of the stuff pushing down on the bodywork.

Each of these elements contributes to creating a bigger challenge for engineers, crews and drivers: setups are adapted, with downforce levels not seen since Monaco on a track that very much resembles Monza; mechanics work hard in hypoxic conditions; and drivers, well, have to stop the car with much less downforce that they’d like to have.

There are many striking elements to the Mexican Grand Prix: a week-long celebration of the country, a party atmosphere from day one to well after the checkered flag, thanks to amazing fans and an attentive race promoter, one of the best podiums in the calendar – but the most crucial of all, just like the rarefied air, is one you can’t touch or see. As the championship enters crunch time, with just five races to go, we will all need to adapt to what our hearts do at altitude: work harder and push for our targets.

Weekend Weather

Friday, October 25: FP1 & FP2

Friday at the Autodromo Hermanos Rodriguez looks dry for the first practice session of the weekend, with temperatures expected to be around 68 degrees F at the local time of 12:30.

There is a zero percent chance of rain for both practice sessions, with FP2 marginally hotter at 72 degrees around 4pm (CST), accompanied by a gentle northern breeze of around 14mph.

Saturday, October 26: FP3 & Qualifying

The final practice session of the weekend will take place under cooler conditions at the earlier start time of 11:30 (CST). Temperatures are expected to reach 64 degrees while wind speeds remain low, and once again there is a zero percent chance of rain.

Qualifying is also expected to be completely dry, while no high winds are expected and temperatures are set to be around a cool 70 degrees F.

Sunday, October 27: Race

Sunday’s race will kick off at 1pm local time (CST), in once again dry and sunny conditions, with temperatures expected to hit 66 degrees F for lights out.

There is a zero percent chance of rain once again during the race, but there may be some rain around in the morning before Sunday’s race

Pirelli Tires

The second stop on Formula 1’s long trip to the Americas takes place in the Mexican capital, Mexico City, before the circus moves onto Sao Paulo to end the run of three consecutive races. At the circuit named in honor of the brothers, Pedro and Ricardo Rodriguez, the available tires are the C3 as Hard, the C4 as Medium and the C5 as Soft, a step softer than in the past, as was already the case last year, the decision taken in order to open up more strategic options for the race.

The first day of track action, Friday 25 October, will be slightly different to usual. The second free practice session will be entirely given over to validating the softer compounds in Pirelli’s 2025 range (C4, C5 and C6) in what is known as an in-competition test. The session is extended by 30 minutes to 90 and all drivers and teams will have to follow a specific program established by the Pirelli engineers. Apart from the dry tire allocation specifically for the Grand Prix (two sets of Hard, three of Medium and seven of Soft, one less than usual), each driver will have two additional sets of tires: one will be identical to the one available for the weekend, to act as a baseline, while the other will be a 2025 prototype option, both in terms of compound and of construction – actually the latter already homologated back in September.

These two sets will not have any sidewall color bands. The plan is for the program to include a performance run and a long run for each set, with every team running the same number of laps with the same quantity of fuel on board, dependent on the type of run. The only exception will be in the case of a regular race driver being replaced for FP1 by a young driver. These race drivers will carry out the Pirelli test for 60 minutes of FP2 only and will have an additional set of Medium compound tires to catch up as much as possible on acquiring data for the rest of the weekend. All the test data will then be analyzed by Pirelli engineers to fine tune the characteristics of the compounds prior to the group test in Abu Dhabi, which starts on the Tuesday after the final round of the 2024 championship. It means that teams will have to prepare their cars for qualifying and the race in the space of two hours: FP1 on Friday and FP3 on Saturday.

The Hermanos Rodriguez track is 4.304 km long, with 17 corners and a surface that is low in terms of its severity on tires. This year the promoter has resurfaced the section between turns 12 and 15 in the third sector. The very smooth asphalt and the fact the track is hardly used means that grip levels are rather low at the start of the weekend and track evolution is very marked, rubbering in the more the cars run.

Mexico City is located at over 2000 meters above sea level and the rarified air has an influence on car performance, reducing the aerodynamic downforce generated by the cars. One of the consequences of this is that top speeds reached are very high, despite a configuration that actually looks typical of tracks that require maximum downforce – the speed record was set here in 2016 when Valtteri Bottas in the Williams-Mercedes was clocked at 372.5 km/h – even if the level of graining is usually quite high. Furthermore, on the longest straights, the main one and the one between turns 3 and 4, the surface temperature of the tires tends to drop pretty quickly and the drivers have to be very careful when braking, especially at turn 1, to avoid locking the wheels and therefore damaging the tires.

In terms of strategy, this is usually a one-stop race. Last year, the majority of drivers tried to manage the Medium to lengthen the first stint as much as possible. A Safety Car and a later red flag, after Kevin Magnussen went off the track in the Haas, meant that nearly the entire field used three sets of tires in a race that was pretty much divided in two.

Formula 1 has always been very popular in Mexico, even if there have only ever been 23 championship races held here, all of them at this circuit in the capital city, inaugurated in 1962. The races took place in three periods: from 1963 to 1970, from 1986 to 1992 and from 2015 onwards. A change of name in 2021 saw the Mexican Grand Prix renamed after the city.

There have been 15 different winners over the 23 editions of this race. Max Verstappen is the most successful driver with five wins, with his Red Bull team on the same number heading the teams’ classification. Jim Clark has started from pole the most often (four times) while Lewis Hamilton has the most podium finishes with six. Of the constructors, Lotus on 6 has the most poles and Ferrari leads the way for podium finishes with 12.