F1: Monaco GP Preview

The Automobile Club de Monaco, having already founded a popular rally, opted to turn the prestigious streets of the Principality into a temporary race facility in 1929, at the wisdom of Antony Noghes. It quickly became a prominent fixture on the motor-racing scene, its status elevated by the challenging layout and desirable location, attracting the elite to the glamorous Riviera. It was included on the inaugural Formula 1 calendar in 1950 and was a permanent fixture from 1955 through 2019, not running in 2020 – its first absence in 65 years – due to the pandemic.

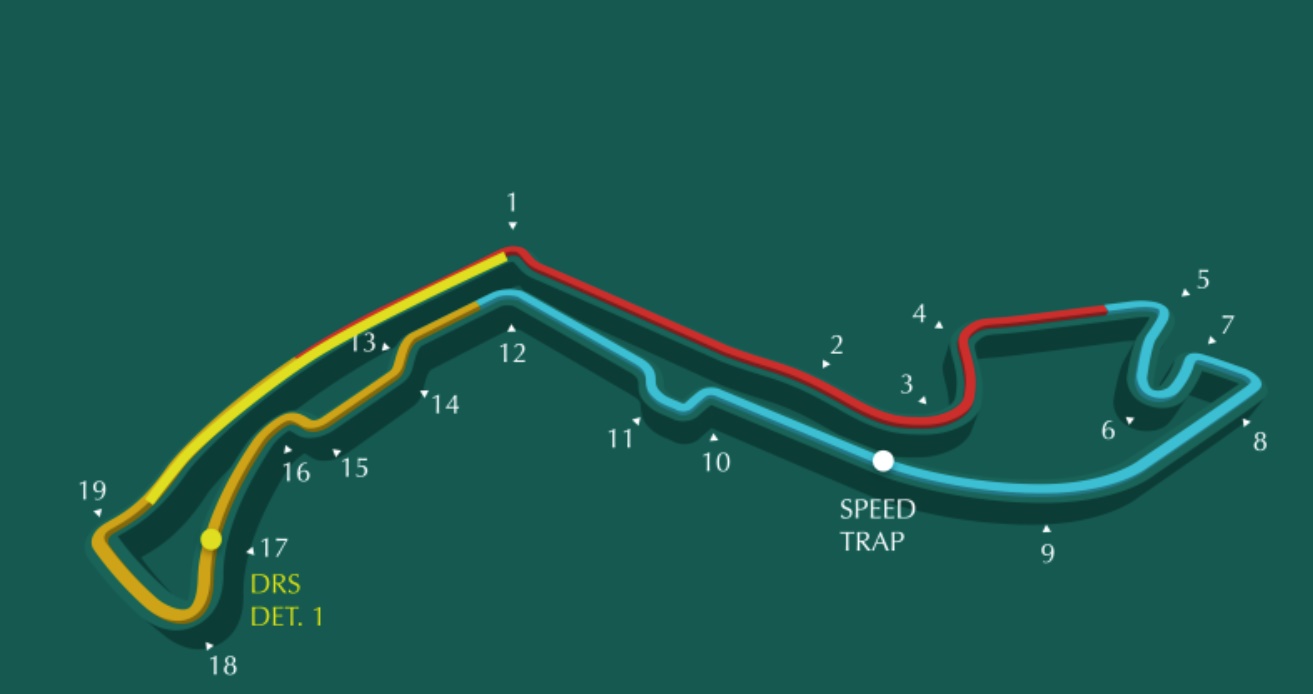

The Circuit de Monaco is a stern test for all drivers given the perilously close nature of the barriers, the evolution of the tarmac across the course of the weekend, and the importance of hooking up a qualifying lap. Track position is of the utmost importance, given that passing is at a premium, while in terms of set-up teams favor mechanical grip.

Finding the limit between brushing the wall and colliding with it is one of motorsport’s greatest spectacles. From Saint Devote through Rascasse and beyond, few tracks test a driver’s abilities like Monaco.

Gone are the days when hay bales, lamp posts and a sheer drop into the harbor would mark the circuit edge, but the layout itself remains largely recognizable when compared to the 1929 layout, taking competitors past iconic landmarks such as the Sainte-Dévote Chapel, Hotel de Paris and Casino de Monte-Carlo.

While at 3.3km it is the shortest circuit on the calendar it is one of the busiest and most challenging for those behind the steering wheel. The margin between delight and despair can be measured in mere millimeters in Monaco.

Keys to the Race

There have been Monaco Grands Prix without a single overtake in the past – which makes strategy all the more important, as races can be won or lost on the pit wall.

• Track position is crucial in Monaco because it’s the toughest place on the calendar for overtaking – and by a significant margin. Qualifying is the key to a strong weekend, and the pitfall is kept busy by the possibility of making up places in the pitlane through strategy, so expect plenty of variance and undercuts as engineers look for tiny, marginal gains.

• Strategy opportunities are boosted by a pitlane time loss of just 20 seconds per stop, not to mention the feasibility of extended stints, despite Pirelli bringing its softest and least durable tires, the C3, C4 and C5. In 2019, drivers managed to eke out tire-life to around 50 laps (of 78) on a single step, so a one-stopper is the preferred option, with the undercut proving all the more powerful.

• Despite the lack of overtaking, the race can be turned on its head in an instant. It’s the shortest race distance of the year – at 260km, compared to 305km for all other Grands Prix – but has the highest chance of a Safety Car (80%) or VSCs (25% of all races, since it was introduced), which means it regularly runs close to the two-hour maximum time-limit.

• It’s just 210m from pole to Turn One (only Austria is shorter), offering limited opportunities to pass. The 2018 and 2019 races combined, excluding lap one and Safety Car restarts, had just six overtakes – all completed without DRS. The best place to try to make an overtake work is at the Turn 10 harbor chicane, where chasing cars are boosted by the long run through the Tunnel and hard braking into a tight left-hander.

What is a Driver’s Workload Like During a Lap?

There are some that say, when watching from the outside, that driving a Formula One car looks easy. But, little do they know the intense workload involved in completing a lap successfully in an F1 car…

What inputs are drivers making during a lap?

Driving an F1 car relies upon the same basic inputs as any car – steering, throttle, gearshifts, brakes – but all with an increased intensity, and with the driver operating under extreme gravitational forces.

On a street circuit like Monaco, the margin for error on those basic inputs is minimal – every element of a driver’s workload on the roads of Monte Carlo is heightened and made all the more difficult by the near-constant twists and turns.

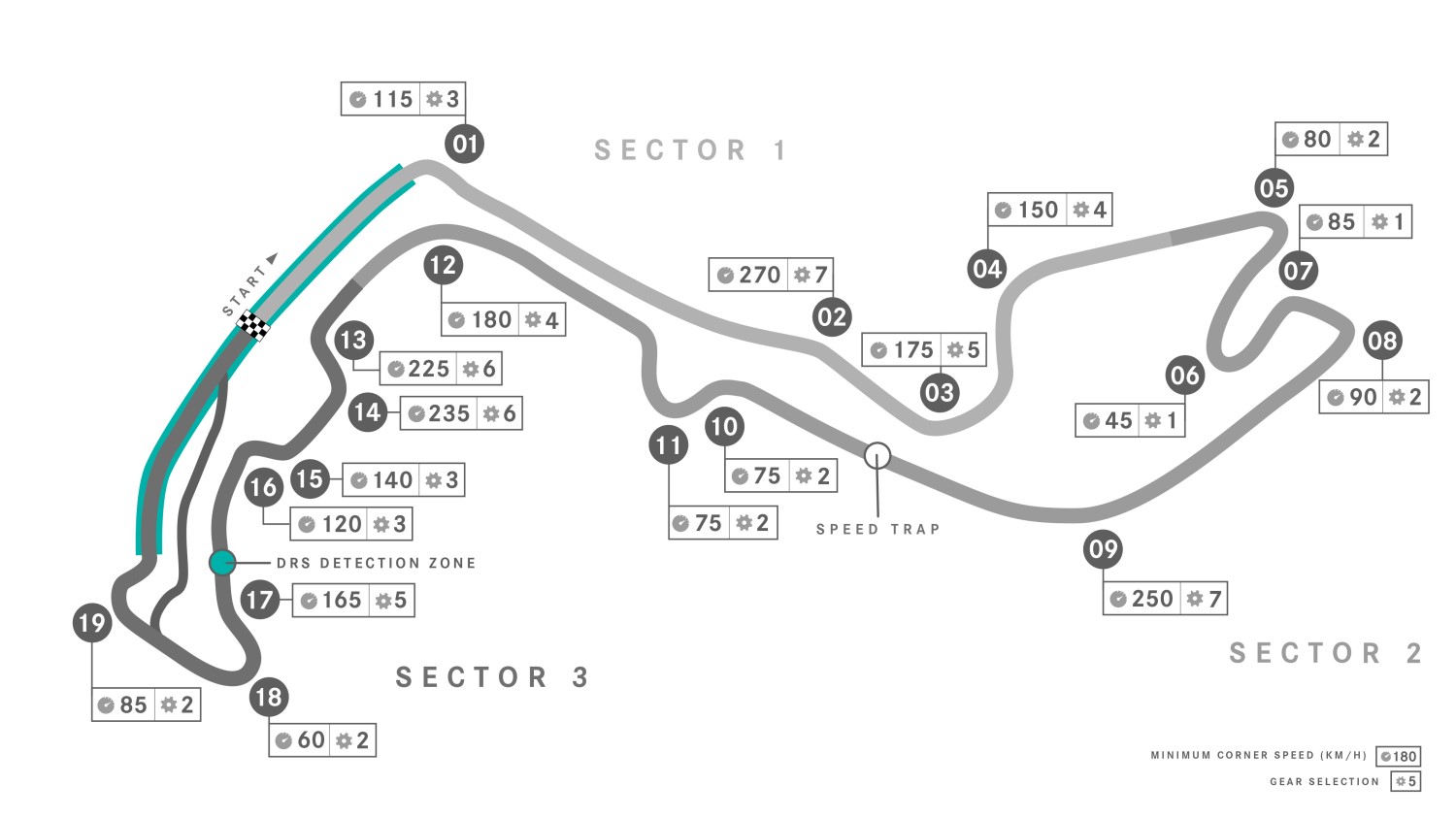

The shift points in particular are a constant focus for drivers. They will make approximately 25 upshifts and 25 downshifts around the 3.337 kilometer Monaco circuit in the just over 70 seconds it takes to complete a lap, and they will be assisted by shift lights on the steering wheel and a beep in their ear to aid timing, in pursuit of every millisecond. Baku has the most gear changes of any track on the F1 calendar, with 70, but this is due to the long straights and considerably longer layout.

With a top speed in Monaco of just 290 km/h, compared to 350 km/h at Monza, the 50 shift changes a driver makes each lap will never involve eighth gear. However, in Monaco, they do use first gear, which is a rarity in F1.

On a modern-day Formula One car, the driver has a multi-function steering wheel allowing a limited range of set-up changes to be made at speed while out on track, from corner to corner. The majority of set-up changes, though, must be made in the garage.

Rotary switches and buttons on the steering wheel enable the driver to adjust a number of set-up variables including brake balance, engine power modes, rates of engine braking, and differential-tweaks to encourage over or understeer.

On a tight circuit like Monaco, there is no classic ‘straight’ entirely free from steering lock – the run into Turn 1 lasts just five seconds and the blast through the Tunnel is seven seconds at high-speed while turning, which makes removing one hand for steering wheel adjustments very challenging. Just 45% of the lap time is spent at full throttle, compared to somewhere like Monza, where drivers spend 78% of the lap time with their foot to the floor on the accelerator pedal.

“It’s all about practice, all about repetitions and preparation,” says Valtteri Bottas. “It doesn’t come easy, but it does get easier, that’s for sure. Some inputs, with practice, become pretty automatic. You are really trying to bring on the muscle memory for certain things and you start to know exactly in which corners you can change the settings for.”

Unwanted driver input is also a factor engineers account for, particularly in Monaco due to the tight hairpin – the slowest corner on the F1 calendar and taken in first gear. The turn requires 180-degrees of steering lock, with the driver’s arms having to cross, which sometimes leads to unintentional button or rotary changes. To combat this, specific guards are put in place on the steering wheel for the Monaco Grand Prix. The design of the buttons and rotary switches themselves are derived from fighter aircraft controls – a similar high-speed, high-stress environment with the operator wearing gloves.

So, while we can all relate to the required inputs of driving a car, every single element is taken to unimaginable and super-human levels in Formula One because of the speed of the machinery and in Monaco, the ever-present dangers of the barriers and walls.

What else is going through the driver’s mind?

While completing a lap, the driver’s vision at high-speed and their ability to react quickly to any changes in the environment is crucial. This is especially challenging at a track like Monaco, which is narrow and twisty, with blind corners and potential surprises around every one of its 19 corners (eight left-handers and 11 right-handers).

As the weekend progresses, the drivers are filtering through different reference points to pick the quickest lines, the latest braking points and progressively build confidence. This is particularly crucial in Monaco, knowing any accidents in the practice sessions could limit their running and even their chances to take part in Qualifying. So, the secret to mastering Monaco really is consistency, building speed throughout the weekend and delivering a continuous crescendo towards that ultimate lap time.

As the driver approaches a corner, the first part of their thought process is picking the line and the route they want to take through the corner. Then the mind starts shifting to the braking zone and where exactly to hit the brakes, and then in that braking phase, it’s all about moving the focus onto the apex and really nailing the line they had decided on. During the apex, they shift focus onto the exit of the corner and that process repeats itself with every turn and every lap. The car can be nervous on exit around Monaco as the car balance is geared towards a precise entry so with a narrow track, the drivers must tread carefully when laying down the power between corners.

“Visually, it’s pretty busy, especially in Monaco,” explained Valtteri. “There’s a lot to look out for, so it’s really challenging, from a mental side of things, and you are all the time picking out different reference points to make you fast.”

With limited overtaking opportunities in Monaco, single lap pace in qualifying is vital which puts pressure on the outlap to ensure the car crosses the start line in optimum shape to begin the timed run. The driver will adjust their brake balance continuously through the outlap while weaving, accelerating and braking to generate temperature in the brakes and tires, while also charging the ERS system so they have maximum power to deploy on the timed lap. The driver will be receiving frequent feedback from their Race Engineer on the radio, keeping their eyes on the mirrors for traffic and selecting the correct power unit mode to achieve the best time.

The workload of a driver at every racetrack does differ depending on whether they are competing in qualifying or the race. In qualifying, everything is about maximum performance and pushing to the absolute limit, so therefore the intensity is at a completely different level. But in the race, the driver is thinking about much more than the absolute performance of the lap, with a more long-term mindset, considering tire management, fuel and energy management, Safety Cars and battles for position also thrown into the mix.

Is Monaco the toughest track for driver workload?

Monaco is a punishing track with no run-offs, just concrete walls and barriers, and the relentless nature of the circuit is what makes it so special, creating a unique challenge for the drivers.

“For me, personally, in terms of workload for the driver, Monaco is the toughest because there is no time to rest” said Valtteri. “It is literally corner after corner, and even the straights aren’t really straight, you are always turning even just a little bit.

“The main straight is the biggest, if not the only, breathing space a driver gets and even that goes pretty quickly in an F1 car! It’s definitely a challenge.”

All F1 tracks come with their own challenges and interesting characteristics, whether it’s on the streets of Monte Carlo or around sweeping, high-speed circuits such as Silverstone or Suzuka, which put the driver through much higher g-forces and include a wider range of corner types.

In Monaco, though, that challenge and intensity is crammed into a super-short, super-quick lap that requires maximum precision and maximum concentration. There’s no relenting. One slip of focus, and the driver and team’s hard work will be wiped away.