F1 Portuguese GP Preview

The FIA Formula 1 World Championship campaign will continue with back-to-back events in Portugal and Spain.

Formula 1 returned to Portugal in 2020, ending a 24-year absence, as the Autodromo International do Algarve, more commonly known as Portimao, made its debut on the calendar. Portimao’s inclusion received widespread approval from fans and competitors alike, with Formula 1 drivers comparing the circuit to a rollercoaster, on account of its flowing layout and series of undulating sections.

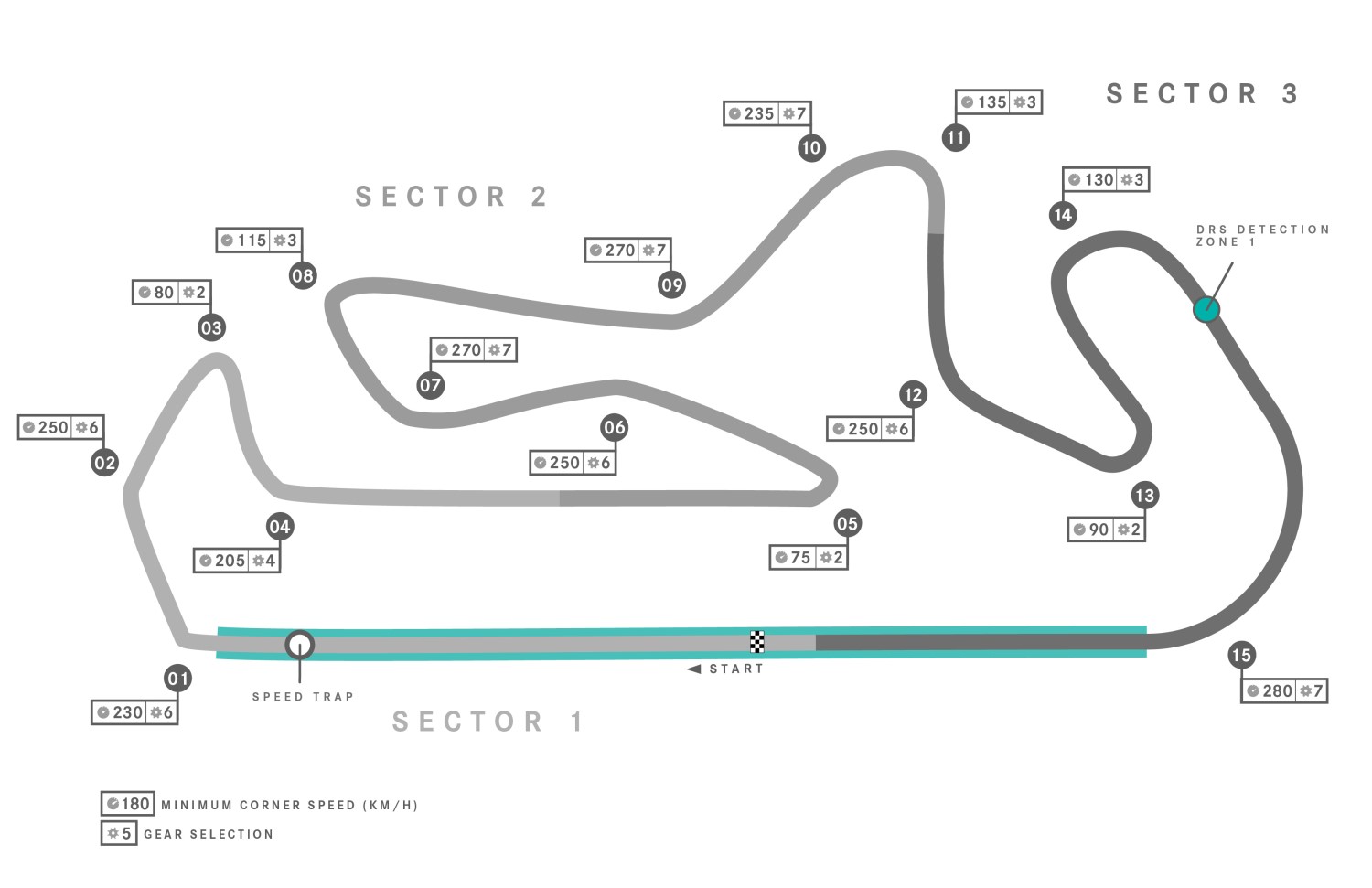

Elevation change is key to the 4.6km lap, with a rollercoaster-ride of blind swooping climbs and swift plunges to contend with, followed by a singular, lengthy DRS zone situated along the pit straight.

Portimão is an excellent circuit, fast and flowing with a lot of elevation change. With the final corner being very quick, the straight is long and fast, especially with DRS. The circuit had been recently resurfaced when we were here last year and that made conditions difficult for the tires. Pirelli have brought the same compounds as last year – the hardest of their range – but the maturing of the tarmac should improve the overall performance.

When the provisional 2021 calendar was unveiled there was a blank space – and it was consequently filled by Portimao, which stays on for another season. But in a change from 2020 it moves from fall to spring as the third round of the campaign, with the event occurring on Portugal’s Dia do Trabalhador – the Labor Day weekend.

The teams will then head across the Iberian Peninsula for the Spanish Grand Prix.

The Circuit de Barcelona-Catalunya is this year celebrating its 30th anniversary, having opened its doors in 1991, as part of the city’s Olympics-focused revitalization. Located to the north of Barcelona the circuit is familiar to the Formula 1 paddock through its longevity on the calendar and its presence as a regular testing venue.

The circuit features a combination of low, medium and high-speed corners while for 2021 there has been a minor tweak to the layout for the first time since 2007, with the Turn 10 complex having been reprofiled. For the 2021 season the Spanish Grand Prix returns to its traditional May date, having been shifted to mid-August in 2020, due to the pandemic.

With a rollercoaster layout and limited data to pull upon, the Portuguese Grand Prix promises to be both eventful and unpredictable. Our strategy engineers have analyzed historic data and more recent car performance to predict the key factors that could determine the result on Sunday.

• Overtaking: Usually one of the easiest circuits on the calendar for overtaking, particularly on the long run down to Turn One. In fact, 49 of the 55 overtakes (89%) made in last year’s Grand Prix came at the opening corner.

• DRS: It plays a vital role here, but changes have been made for this year’s race. The start/finish line’s DRS zone is reduced by 165m, which could impact passing into Turn One. But a secondary zone has been added on the straight between Turns Four and Turn Five, with the latter corner already a hotspot for overtaking.

• Run-off: Portimão is the opposite of Imola when it comes to track limits – it has sweeping expanses of smooth run-off. While Imola is particularly punishing, so is Portimão – except it’s the stewards who tend to be kept busy. In 2020, 194 laps were deleted for infringements – that compares to 63 in Imola last time out.

• While there were no Safety Cars in last year’s race, there were three red flags in practice and the low-grip surface created a surprising start to the Grand Prix as drivers struggled for traction away from the line. Expect incidents!

• Strategy: It’s likely to be a uniform one-stopper due to low tire degradation. Last year, most drivers chose to pit just once – the only exceptions being those affected by an issue or hit with a penalty. Pirelli is bringing its C1, C2 and C3 tires this weekend, the hardest range available

Technical Analysis

The majority of the 969m start/finish line opens the lap at Portimão, with drivers carrying significant speed into a tricky, bowl-shaped right-hander at Turn One. With plenty of opportunity for slipstreaming, it’s the key place to overtake – but also very easy to run wide and pick up a stewards’ warning.

It’s simple to follow Turn Two’s flat-out kink by going wide into Turn Three, Lagos. It’s the slowest corner on the track – and is unusually wide for such a big stop. The tight and technical second and third sectors mean most battles are usually resolved by Turn Five.

Portimão is notable for its swoops and dives. On average, tracks feature gradient changes of around 8 per cent – the steepest gradient at Portimão is a 16 per cent downhill slope, with the track sweeping steeply downhill between Turns Eight and Nine and 11 and 12.

Sagres corner (Turn 14) requires a late turn-in followed by a wide exit is key as drivers sweep into the final corner, Galp. This turn starts off blind, but drivers can gather speed through the apex all the way through to the finish line. It also takes precision to excel here on an in-lap – with the pit entry placed at a tricky angle.

Expect top speeds of over 352km/h (219mph) on the main straight.

The Impact of Track Elevation in F1

One of Portimão’s most distinctive characteristics is the frequent elevation change, with the circuit rising and falling dramatically throughout the course of the lap like a rollercoaster.

These gradient changes are far steeper than they appear on TV, but although they don’t pose a technical challenge to the cars themselves, they have a much bigger impact for the drivers…

How does elevation change influence how the car performs?

The simple answer is that elevation change does not impact the performance of the car as much as you might expect. It does put a little more strain through the cars, but they are built to handle heavy curb strikes and large forces anyway, so a bit of extra compression in the suspension is no bother for modern-day F1 machines.

But different types of elevation change impact the cars in different ways, depending on the circuit and the topography. Some will require tweaks to be made to the car set-up, to really dial the car into the track characteristics and maximize them, while others will require the right compromise to be found.

Take Spa-Francorchamps as one example. The intense downhill and uphill complex of the Raidillon de l’Eau Rouge requires teams to increase the front ride height of the car. This is to handle the vertical compression forces of around 3g that the car is experiencing, as it is pushed into the ground through the sudden downhill-to-uphill change while at almost vMax (maximum velocity, otherwise known as top speed).

The vertical compression of the tires and suspension through this section of track is one of the highest on the calendar, which isn’t particularly surprising considering Spa has the biggest difference in elevation change (102 meters between the highest and lowest point) in F1.

Yet this level of compression isn’t a consideration at a track like Portimão, because while there are some steep slopes, the elevation changes aren’t taken at such high speeds. The elevation change from lowest to highest point is also not as dramatic as a track like Spa, with a difference of just under 30 meters, but the ups and downs are more frequent.

However, these undulations do still have an influence on how the car handles and reacts during a lap. First, at Portimão there are uphill and downhill corner entries and exits, so a mix of gradient directions. You can’t set the car up for one or the other, because that’ll compromise too many of the other elements, so a middle ground has to be found to ensure the car reacts well enough in all of those scenarios.

Second, an interesting factor in Portimão are those downhill corner exits. The loads of the car go ‘light’ on exits such as Turn 11, which has a 16-metre drop, the steepest decline in gradient at the track, and the car effectively just wants to go straight on. It doesn’t because of gravity and downforce, but the drivers still feel a noticeable lack of grip and this can make the car more unstable. It also makes traction trickier, so there is a delay with the drivers getting the power down.

Another track with some obvious elevation change is the Red Bull Ring in Austria. The cars don’t experience compression or the ‘light’ feeling here, but there is track ‘warp’ to contend with. This is where there are different gradients on the track left to right, as you go along, effectively creating a spiral effect.

Turn 3 in Austria is a clear example of this, because the corner creates a crest – from the uphill entry and downhill exit. As drivers navigate this warp, the car tends to want one wheel (the inside front on this occasion) to get some air and this upsets the car balance.

What challenges do elevation changes provide the drivers?

Looking specifically at Portimão, the elevation change has a much bigger impact on the drivers than it does the cars. The undulations create some blind corner apexes, including Turns 8, 11 and 13. This makes it tougher for them to see the entries to the corners and create reference points for braking and turning in.

Because of this, it can make it more difficult to learn the track and build up speed during those initial laps in practice. This is certainly something we found last year, on our first visit to Portimão, where it took a little longer during practice for the drivers to settle in and know where they need to commit to their racing lines and braking points.

Arguably the trickiest complex for the drivers is Turn 10 and 11 because it is a double-right hander with a blind entry – as the track rises by roughly 12 meters – and a steep downhill drop on the exit of 16 meters. The steeper the slope, the more an F1 car wants to become airborne. But it doesn’t due to gravity and downforce.

However, the load under the tires (called the contact patch) reduces as a result and this impacts the grip the driver has on the exit. So, it does make the car a bit more unpredictable at these points on tracks like Portimão, where there is a dramatic drop in gradient.

The unsighted entry to the Turn 10/11 sequence and track width means we see plenty of different approaches by the drivers – particularly during practice, where they are finding the limit. Even with the blind entry though, over time and with experience, they know exactly where to point the car.

The elevation changes do put a little bit more force through the driver’s body and make things more physically demanding during a lap. While this isn’t too severe an issue in Portimão, owing to the speed the drivers tackle the crests and troughs, at a circuit like Spa-Francorchamps, this is a different story.

The sweep through the Raidillon de l’Eau Rouge, for example, is a massive compression. Just as it puts more forces through the car and its components, additional forces are also being experienced by the driver too. Thankfully for the drivers, where elevation is concerned, these are short, sharp bursts of additional force rather than more sustained forces experienced through cornering.

Do elevation changes also impact the racing?

The undulating nature of some tracks does have a small but important impact on the racing itself. For example, in Portimão the elevation changes and unsighted entries to certain corners create more than one line, which can create opportunities for overtaking or mistakes. But it can also make the racing line even more defined, depending on the local topography.

Safety and visibility are further factors for the drivers to consider, as there are several sections that are unsighted. The dip before the first corner is one such example at Portimão, as is the drop after Turn 8, where you cannot see what is ahead until you peek over the crest. These are all further challenges and thought processes being added to the drivers’ workload during the sessions.

The blind corner entries also increase the risk of mistakes in Qualifying as the drivers are picking braking or turn-in points without the normal track reference points that they’d have in clear sight. So, it is tougher to be precise, particularly when on the limit during Qualifying at a track like Portimão.