F1 Turkish Grand Prix Preview

After a week off, Formula One heads to Intercity Istanbul Park, one of Hermann Tilke’s finest creations. The circuit had not hosted a Formula One race in nine years before being announced to return for the 2020 Formula One World Championship after major schedule changes as a result of the COVID-19 pandemic.

Turkey acts as the meeting point of two continents as it is where Europe meets Asia across the Bosporus strait, which is straddled by the historic city of Istanbul. On the eastern outskirts of the sprawling metropolis, home to 15 million people, sits the Intercity Istanbul Park circuit, which hosted Formula 1’s Turkish Grand Prix between 2005 and 2011. Now, following a nine-year absence, the track has returned to the championship to host Round 14 of this year’s 17-race campaign.

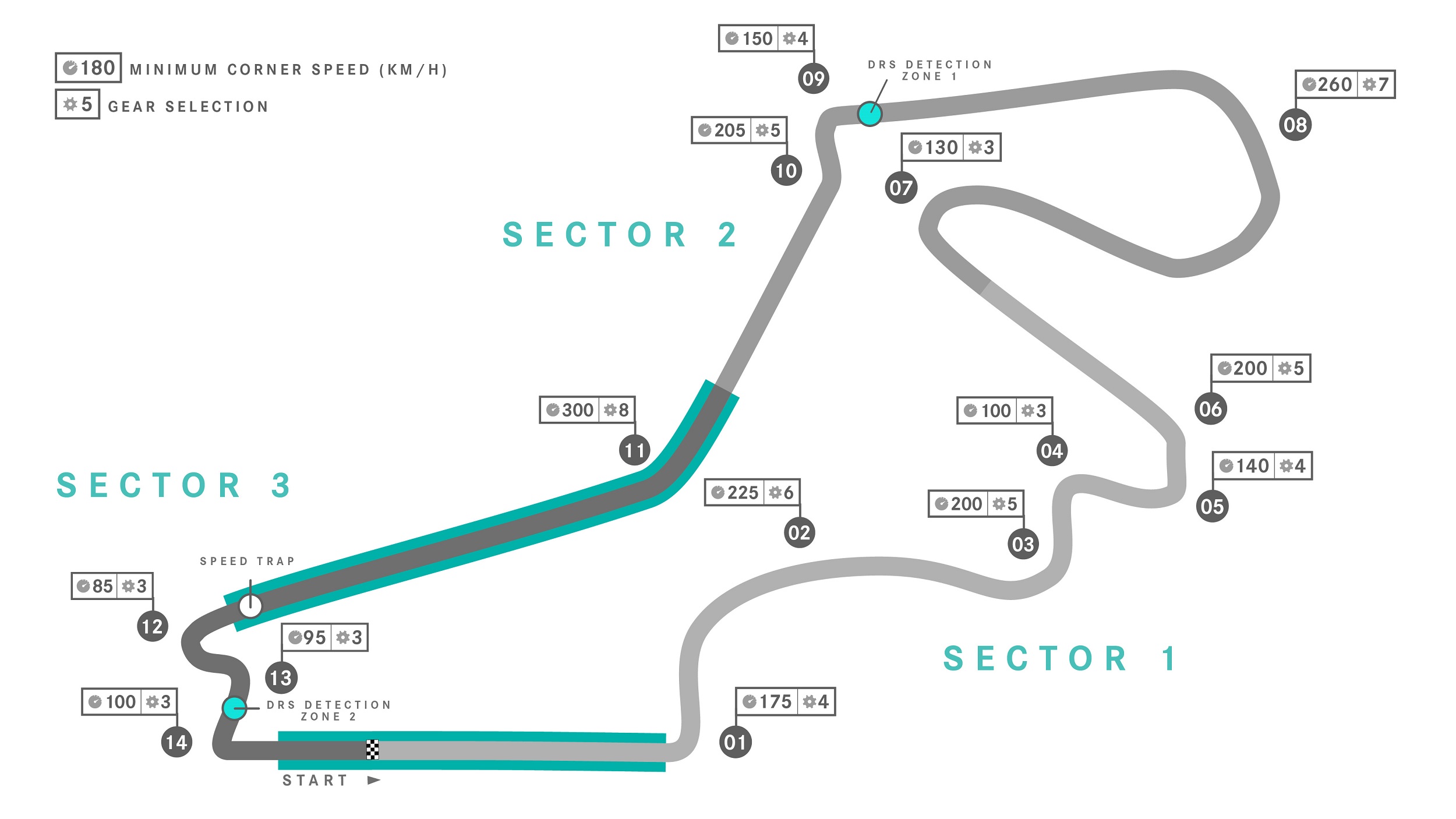

The 5.3km circuit was widely acclaimed during its first stint on Formula 1’s schedule, with the opening complex of corners drawing comparisons with the iconic ‘Senna S’ plunge at Interlagos, and the quadruple apex left- hander at Turn 8 proving a stern test of car and driver alike. The wide nature of the track, allied with long straights and heavy braking zones, means a large number of overtakes are eminently likely.

Dave Robson, Head of Vehicle Performance For Williams F1: The circuit at Istanbul has one of the best layouts of the circuits added to the calendar in the last 20 years. Like Imola, it runs anticlockwise and uses elevation changes to enhance the challenge and spectacle. The famous Turn 8 is the signature corner on the circuit and will subject the cars and drivers to large lateral forces for a sustained period, adding to the physical challenge.

AlphaTauri Race Preview

Turkish Grand Prix weather forecast

FRIDAY, NOVEMBER 13 – FP1 AND FP2 WEATHER

Conditions: A mix of low-level clouds and sunny spells. Dry conditions very likely. Light wind.

Maximum temperature expected: 17 Celsius__

Chance of rain: <20%

SATURDAY, NOVEMBER 14 – FP3 AND QUALIFYING WEATHER

Conditions: Mainly cloudy. Moderate chance of light scattered showers, most likely in the afternoon and evening. Light-to-moderate northerly wind.

Maximum temperature expected: 16 Celsius

Chance of rain: 40%

SUNDAY, NOVEMBER 15 – RACE WEATHER

Conditions: Mainly cloudy all day long. Moderate chance of light scattered showers. Air temperature around 15°C during the Race. Light northeasterly wind.

Maximum temperature expected: 15 Celsius

Chance of rain: 40%

Five things to look for

- Formula 1 is returning to Turkey for the first time since 2011 – meaning some teams can rely on previous data, but this will be limited by the continual evolution of F1 cars since then.

- Another factor that will impact previous data is the timing of the race. Turkey will host its Grand Prix return in November, whereas the race was previously held in May. While track temperatures could in the past exceed 40C, it’s likely to be in the 20C-range this weekend.

- The iconic Turn 8 is more than just a spectacular corner and will be hugely demanding on the drivers. Through Turn 8, each driver will likely spend six seconds at a sustained lateral G-force exceeding 3g every lap of the 58-lap Grand Prix.

- Turn 8 will likely influence the stint lengths in the race too, with the right-front tire particularly stressed. Turn 8 is best taken flat and, with a long straight following it, any conservative approach through the corner to help extend tire life could end up costing track position and lap time.

- Istanbul has a reasonable mix of corner speeds, with the majority falling in the medium-speed range. Teams are likely to spend practice trying to find the optimum downforce level because the long straights will potentially tempt some into lowering drag as a result, despite there being some corners where load will be important. It’s a fine balancing act for set-up.

How has F1 changed since the sport last raced in Turkey?

It’s been nine years since Formula One’s most recent race at the Intercity Istanbul Park in Turkey and the sport has changed considerably compared to 2011.

But, just how much have the cars and technology evolved in that timeframe? There are clear visual differences, largely down to regulation changes, with the cars being wider and longer in 2020, with larger wings, lower noses and the addition of the halo. But the differences go much deeper than that – so we’re taking a look underneath the bodywork to find out how much F1 has changed in less than a decade.

How much has the engine technology evolved in these cars, since 2011?

They’ve changed completely. The engine of 2011 was a naturally aspirated 2.4-liter V8 that revved to 18,000 rpm and weighed at least 95kg. It included early hybrid technology with the KERS unit, which harvested kinetic energy from the car under braking. This gave the driver an additional 80hp for 6.7 seconds per lap, which he could deploy when needed. KERS boosted the engine’s peak power output to around 815hp.

Fast-forward to present day and an F1 car’s source of power is remarkably different. Since the introduction of hybrid regulations in 2014, the sport has used turbocharged 1.6-liter V6 Power Units which hit the scales at 145kg (minimum regulation weight) and rev up to 15,000 rpm. Peak power is considerably higher with today’s PUs producing well over 100 hp more than those in 2011 – while being way more efficient at the same time. An F1 Power Unit in 2020 achieves a thermal efficiency – the amount of fuel energy converted into useful work – of more than 50 percent, compared to around 30 percent in 2011.

The increase in power, the higher efficiency and the higher weight are largely down to the sophisticated hybrid system used in F1 today – made up of the Energy Store (ES), Control Electronics (CE) and two sources of additional power, the Motor Generator Unit Kinetic (MGU-K), generating power from brake energy, and the Motor Generator Unit Heat (MGU-H), producing power from the exhaust gases. The additional electric power from the ERS system is deployed through the lap, giving the driver more hybrid power for longer compared to the quick boost from the KERS unit in 2011.

The modern hybrid system also improves the drivability of the car as the electrical system can deliver instantaneous torque. This can be used to smoothen the power curve from the ICE, for example during upshifts.

Today’s engines also have to be much more reliable: In 2011, each car had eight engines to use across the 19 races; today, teams are limited to a much smaller allocation of each Power Unit component across a season, with three Internal Combustion Engines, Turbochargers and MGU-H units and two MGU-K, ES and CE units.

What else has changed under the skin of the cars?

Something that isn’t so obvious is the electronics on the car, where technology has gone through a major advancement in the last decade. One example of how much the electronics on the car have evolved is looking at data. In 2011, F1 cars logged around 500 channels of data. In 2020, cars are limited to 1,500 high-rate channels and many thousands of background channels, too. The increased data logging also has an impact on the amount of data a single car collects over a race weekend. In 2011, the Turkish Grand Prix weekend would amount to around 18GB per car. Today, this will be closer to 70GB.

The car’s electronic layout has changed a lot, too, with an increased use of small sensor nodes around the car. These are each capable of acquiring data from many sensors and communicating back to a central datalogger. Wireless sensor technology has undergone a vast improvement, allowing an increased use of small, wireless nodes for data gathering and wireless offloading of data generated on test or practice days. One example is the tire pressure monitoring systems, which were quite bulky in 2011 and transmitted in the 400MHz range. Today, the sensors are smaller, with higher frequency transmission and lower battery use – an evolution that our Electronics department compare with going from a walky-talky to a smartphone!

Another example is the way in which the teams gather tire temperature information. In 2011, we ran large, external infrared cameras. Now, the sensors are completely integrated and give drivers access to multipoint tire temperature information at all times.

How do the cars stack up and compare, when it comes to pure numbers?

Regulation changes over the years have created the considerably chunkier F1 cars raced in 2020. They now measure in at over 5,000mm in length, compared to 4,800mm in 2011. Present-day cars are wider, too, taking up more track width at 2,000mm compared to 1,800mm in 2011. They’re also heavier, in part due to the higher weight of the Hybrid Power Units. F1 cars hit the scales at 640kg in 2011, whereas 2020-spec cars now weigh at least 746kg.

But the cars haven’t just grown in size, they also produce considerably more downforce. That means that the tire loads have increased a lot. Around a lap of Istanbul Park, we’re expecting the front and rear tires to see around 50% more load compared to 2011. And when you focus specifically on Turn 8, the front-right and rear-right tire will have a 30 to 40% increase in load.

It’s also worth noting that the tires have changed considerably, too. The last Turkish GP took place in Pirelli’s first season as F1’s sole tire supplier, so the construction and structure of the tires has changed since then. The tires are also wider now, having increased around 25 percent in size through the introduction of the 2017 regulation change. With a bigger contact patch on the ground, the tires can generate more grip and thus quicker lap times.

What does this all mean in terms of lap times?

In 2011, Sebastian Vettel took pole position for Red Bull at the Turkish GP with a 1:25.049. We expect that the 2020 cars with their increased power and higher downforce, will be around four seconds quicker in Qualifying trim. And while the session format itself hasn’t changed much since 2011, some of the rules and technology around Qualifying has.

For example, Vettel’s lap time at Istanbul Park in 2011 was set with unlimited DRS use, whereas today there are only two designated DRS zones at the track. However, drivers had less energy deployment from KERS (only 6.7s per lap) in 2011. Fast forward to 2020 and the energy deployment from the ERS system is being utilized through the entire lap.

What can we expect from the Turkish GP track, in 2020?

The higher cornering speeds and the subsequent higher lateral g-forces will make the track a more physically demanding challenge this year for the drivers. Braking and cornering can reach up to 5g whereas nine years ago, it was around 4g, and those stronger g-forces really add up.

With the current spec of Pirelli tire, where we’ll have the three hardest compounds in the range in Turkey, we’re expecting it to be tricky to get the tires up to temperature with these modern cars – which is the opposite issue to what we experienced in Turkey back in 2011.

Due to the increased downforce levels, the iconic Turn 8 will be less of a focus than before. It was pretty much flat-out in the 2011 cars, but it will become even less of a challenge in these 2020 machines. So, teams don’t need to compromise the setup so much for it.

Unlike some other unfamiliar races on the 2020 F1 schedule, we do actually have some historical data for the Turkish Grand Prix. However, because the cars have changed so much and the track has recently been resurfaced, the historic data is only useful as a reference.