2020 Portuguese Grand Prix – Preview

F1 teams get ready for their maiden visit to the country, which returns to the Formula 1 World Championship after a 24-year absence.

City-based courses in Porto and Lisbon both played host to grands prix in the early years of the championship but it was in 1984 when the Portuguese Grand Prix (shown above) sparked into life at a facility located on the outskirts of the capital city in Estoril. The likes of Alain Prost, Ayrton Senna and Michael Schumacher all triumphed at the circuit but after 1996 Formula 1 sought pastures new, and Portugal was left out in the cold.

Fast-forward to 2020 and Portugal is back in the fold, only this time the Autodromo Internacional do Algarve – also referred to as Portimao in deference to the nearby coastal town – is the venue for world championship competition. It will be the first time that a Formula 1 grand prix has taken place at Portimao and it will be the second brand-new venue on the 2020 calendar after September’s trip to Italy’s Mugello.

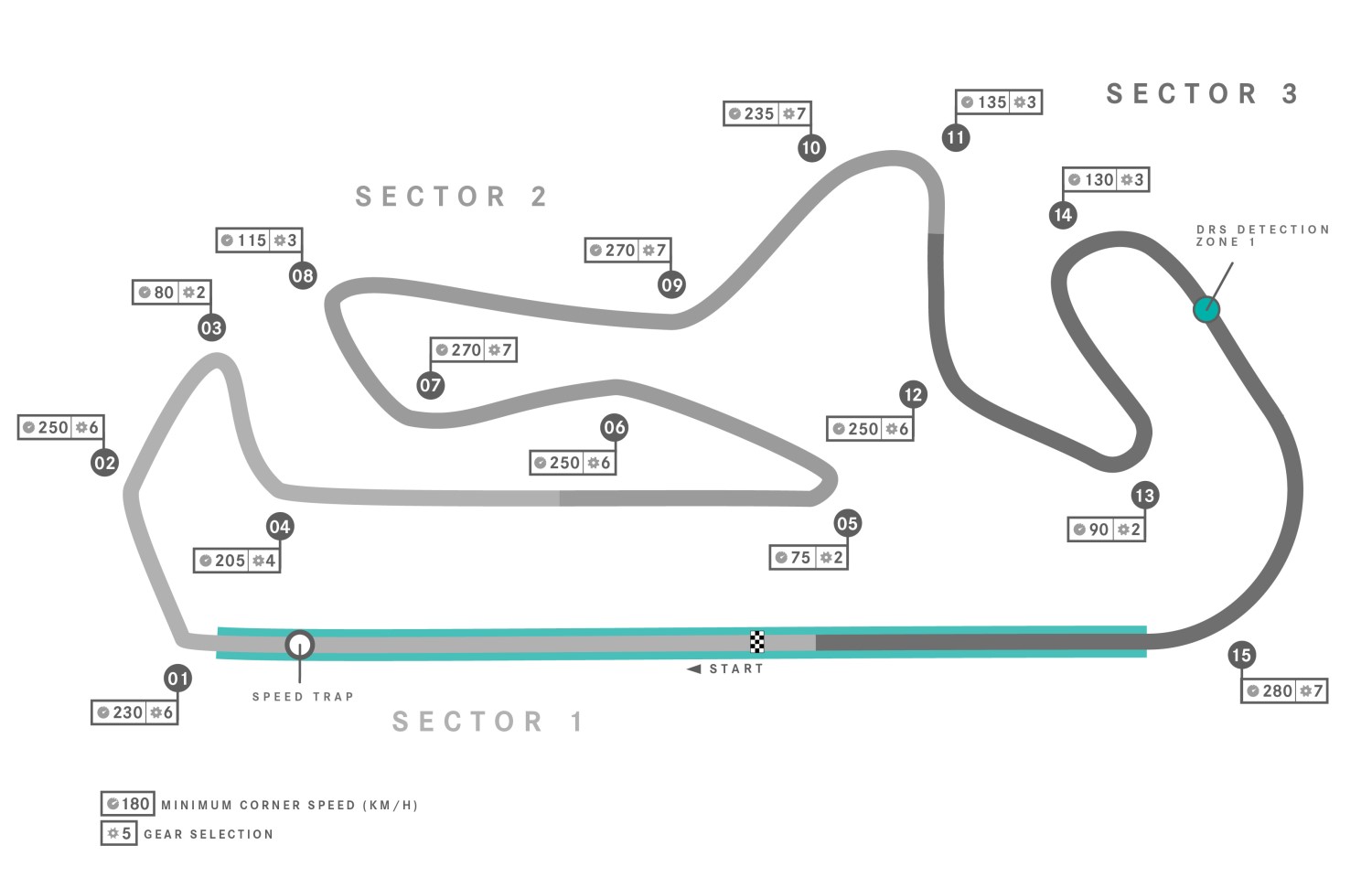

The recently resurfaced 15-turn 4.653km-circuit is renowned for its medium and high-speed sections, relative width that promotes various racing lines, and undulating topography that enhances the challenge. Neither Romain Grosjean nor Kevin Magnussen have raced on the sweeping curves of the Algarve venue and thus it is completely new territory for Haas F1 Team and its drivers, as the team strives to add more points to its 2020 tally.

Going to the Autódromo Internacional do Algarve will have a different flavour. For more than a decade the track, commonly known as Portimão due to the name of the nearby town in southern Portugal, has been touted as a possible venue for Formula One, hosting testing sessions and shakedowns and featuring on the calendar in GP2: nothing came of all the rumours and hopes, however, and the Formula One train seemed to have passed this venue by – until now.

This may be the first appearance for this track on the F1 calendar, but Portugal boasts a proud history in the sport. Stirling Moss and Jack Brabham won in the first World Championship races staged in the country, in the ‘50s, before the Circuito do Estoril, the home of the race from 1984 to 1996, saw legendary names such as Alain Prost, Nigel Mansell and Michael Schumacher added to the victors’ list. The track was the scene of several firsts, notably Ayrton Senna’s maiden win, in 1985, and David Coulthard’s first success ten years later, before being struck off the calendar ahead of the 1997 season.

A circuit famed for its changes of elevations and propensity to create good racing, the Algarve Circuit has been compared to the Nürburgring; the undulating nature reminds us of Mugello, too: and since these are the two tracks on which we have most recently scored points, we can only hope for a case of same actors, different venue, same end result…

The Portuguese Grand Prix will take place from October 23 to 25, with two 90-minute practice sessions on Friday, final practice and a three-part qualifying hour on Saturday, the results of which set the grid for Sunday’s 66-lap grand prix. Lights out is due for 13:10 local time (09:10 EST/13:10 GMT).

Dave Robson, Williams Head of Vehicle Performance on the track

The twelfth event of the 2020 season takes place at the Algarve International Circuit, Portugal and is the first time that Formula One has raced in Portugal since 1996. The circuit – near Portimao – is a modern facility with an interesting layout, reminiscent of Barcelona, but with much more elevation change. The final high-speed corner, which returns the cars to the main straight is likely to become a favourite with the drivers.

We are looking forward to the challenge of another new circuit, having enjoyed the experience in Mugello and the Nürburgring. Losing the Friday running in Germany has left us with a lot of work to get through this weekend, and in addition to our own testing, we will complete some tire testing for Pirelli during the opening 30 minutes of FP2.

Pirelli have brought their hardest tire compounds to this event and have also brought more Hard tires than usual. Depending on the nature of the asphalt and the temperature we find, this may prove to be quite conservative. However, as it is the same for all teams, then it is something that we will need to embrace and make the most of. The tire grip will dictate the downforce level that teams choose to run and one of our main objectives on Friday will be to understand the trades of different rear wing levels. We have some new aerodynamic test parts this weekend and the drivers will share the programme to understand if the new components are behaving as expected.

Track Characteristics

- The undulating track contains 15 corners and a long straight, with the final very long right-hand corner (Galp) putting a lot of energy in particular through the tires.

- There’s quite a wide mix of corners: one of the reasons why Portimao was selected as an F1 testing venue heading into the 2009 season. The tires are subjected to both lateral and especially longitudinal energy demands due to heavy braking, which will provide a considerable challenge. As usual with any new circuit, the data gathered in free practice will be vital in terms of establishing this information and formulating the right strategy.

- The circuit is quite wide at up to 14 meters, which should help overtaking.

- The track was completely resurfaced a few weeks ago so the new asphalt is an unknown: which could have different characteristics to the previous surface

Fast Facts: Portuguese Grand Prix

- One of the most striking characteristics of Portimão is the elevation change, with the track rising and falling frequently – and on occasion, quite steeply – throughout the lap.

- The undulations create some blind corner apexes and exits, which can make it tougher to learn the circuit and build up speed during those initial laps.

- We’re expecting overtaking to be tricky in Portugal due to the flowing nature of the track and lack of heavy braking zones. The only DRS zone is on the main straight and the quick final corner will make it harder for cars to keep a tight gap. The zone itself is very long, so this should give drivers the chance to close up on their rivals.

- The Turn 10/11 complex is anticipated to be the most challenging part of the circuit for the drivers, because it’s a double-right with a blind entry and a downhill drop on exit.

- However, there’s also an unknown ahead of the event as to whether Turn 10 should actually be classified as a corner – some maps of the track do so, therefore giving the track 15 corners, while others say it isn’t and state there are only 14.

- On paper, the track layout itself should suit higher downforce levels but because of the long main straight, we’re likely to see teams trialing different wing settings in practice to decide where the compromise is – being faster in the corners or protecting yourself on the long straight.

Featured This Week: How Does Mercedes F1 Simulation Work?

F1 cars are the most sophisticated automotive machines in the world – and yet, testing them on track or in the wind tunnel is extremely limited. There are only six days of pre-season testing and each race weekend comes with only four hours of practice. That’s why Formula One teams rely on gathering data in the virtual world more than ever before – and a big part of that work is simulation. This area has become even more crucial during the 2020 season, because of the many new tracks on the calendar.

What types of simulation do F1 teams use?

There are a few areas of simulation that F1 teams use to prepare for a Grand Prix weekend, but the two main ones are driver-in-loop and computer simulation. Driver-in-loop (DiL) is effectively our virtual test track, where our car and the tracks we race on are modelled in incredible detail, to enable us to develop the car, find the right set-up direction and help the drivers familiarise themselves with a track in a virtual environment. We use a bespoke simulator facility at the factory and the DiL is somewhat similar to a professional airplane simulator used for pilot training – with the obvious difference that our “cockpit” looks like an F1 car, not a flight deck. In a typical DiL session, our race and simulator drivers can easily complete more than a full race distance. However, in that same space of time we can log thousands of computer simulations as computer simulated laps can be done 100% virtually. That means they can be sped up and run in parallel with other simulations to support both the vehicle dynamics and the strategy groups. The value of these different virtual tools is critical for an F1 team, particularly when we’ve never raced at the track before.

How accurate is the Driver in Loop simulator?

The track models that we use are highly detailed. They are generated by lidar scanning, where laser imaging is used to create a 3D map of the entire circuit and all of its characteristics – from track surface to kerbs and even the environment around it. F1 teams also work with gaming companies to make the track environment as realistic as possible, as visual cues are important for the drivers to determine braking points or the right moment to start turning the car. The market for these highly complex track models is fairly small, so multiple teams will often base their simulations on the same track data and information. The simulator itself is designed to be as realistic as possible with the same chassis, cockpit, steering wheel and pedals as the car itself, and drivers will often run in full race kit to really immerse themselves in the experience. A significant amount of time is spent correlating the virtual model of the car to the car in the real world, so that the car can handle in the simulator just like it does out on track. This allows us to run through set-up tweaks and changes to the car, as we would at the track, to see how it changes balance and performance.

Why is the Driver in Loop simulator so important and does our approach change for new tracks?

It’s an incredibly important part of our preparations and it’s especially vital when visiting a new track, where you have little to no historic data. While our approach remains the same, it does mean the team is more dependent on gathering information in the simulator and as a result new circuits require a more extensive programme. For a track that we’ve visited before, we’ll typically dedicate a two-day programme in the build-up to the event, equating to around 450 laps and roughly eight race distances. The majority of the running is completed by our team of simulator drivers, but Lewis and Valtteri also use the facility. However, when it’s a new circuit, the amount of work is much higher, with two additional days in the run-up to the event plus another day dedicated to the race drivers learning the track layout. The bulk of the work is completed in the build-up to the race weekend, but the work doesn’t stop when the team arrives trackside. The simulator department also run a Friday programme for each Grand Prix, supporting the drivers and engineers at the track to really maximise the learnings from the first day of action. And once the weekend is over, the sim is fired back up to conduct a post-event programme to further understand race performance and assess potential improvements. All of this crucial pre-event work is conducted to ensure the team arrives at the track with the car in a good enough place that the drivers can begin pushing hard from the very first laps.

How do teams use computer simulations to gather information?

Alongside the DiL programme is another virtual test track, but this time, it lives completely inside the computer itself. A racing line file is generated from the DiL to create a single trajectory around the lap and this racing line is used to complete hundreds of thousands of virtual laps ahead of each event, producing a few terabytes of data. The engineers are able to speed up these computer simulations and run them in parallel with one another, with this much faster pace allowing a vast amount more information to be gathered in a much smaller amount of time. From the vehicle dynamics side of things, engineers are really focused on the details – both in getting information on very specific parts, but also seeing how the car reacts to very small set-up changes. A huge number of set-up possibilities are run through the simulations and the data output – often in the form of a graph – can be compared, not only from the other runs but also overlaid on top of the DiL or real car information. Our technical partners play a crucial role in our computer simulation capabilities, with HPE providing data centre infrastructure and hardware, Pure Storage bringing storage solutions and TIBCO giving us the mechanisms to visualise and report the findings from our simulations. Once the data has been analysed, the team then decide what direction to take with the car set-up for Friday’s practice sessions and this will be used as a base to start the development of the car out on track.

What other areas of the team use computer simulation?

Another critical area for simulation is strategy. The computing models used for these strategy simulations feature all drivers and teams, but also include assumptions for pit stop scenarios and the variables of the circuit, such as pit stop loss, tire degradation and car competitiveness. These are bundled into the computer simulations with some realistic element of variability to account for a wide variety of situations, which run many different race and Qualifying session scenarios in order to work out the best strategic options – from which tires to use, to what lap to pit and how to react to losing or gaining places at the start. Running this vast array of strategy simulations is also useful for working out the programme for Friday’s practice sessions, revealing what information will need to be gathered or what details the team is missing. Before we’ve even turned a wheel at the track, hundreds of thousands of strategy simulations will have taken place in order to put the strategy team in the best possible position heading into these live sessions.

What challenges have teams faced during this unusual season?

One of the most obvious challenges that teams have faced this season is the sheer volume of new circuits to prepare for. Typically, a new season will include one brand-new track. Simulation work for these unknown circuits start as soon as the calendar is confirmed, usually six to eight months in advance. However, this season the schedule has been ever-changing and races have only been confirmed two or three months ahead of their planned dates. And of course, from the 17 confirmed races, three layouts (Mugello, Portimão and the Bahrain Outer Circuit) have never been raced on by F1 before and three others (Nürburgring, Imola and Turkey) haven’t been visited by F1 for quite some time. So, it’s much harder to gather the same volume of information as usual due to the tighter timeframes.

Can these methods simulate everything?

We aim to gather the most accurate info we can from the DiL and computer simulations, in order to be in the best shape possible, come FP1. But of course, these simulations can never be 100% accurate and are only as good as the data that’s put into them. Because of this, simulations are never used to finalise decisions, but instead used to assist and influence the direction that the engineers go down. Once the path has been chosen, it is then down to the drivers to provide real-world feedback and for the engineers to take this information onto the next level. The full car model can never be perfectly accurate, and you also can’t model the grip of the tarmac and how the tire responds to it. Some aspects of the car set-up, such as wing levels, are easier to gather information on through simulations while others, such as car balance or grip levels, are more difficult because they depend on more factors – some of which are outside your control, such as the weather. We can make assumptions for the simulations, but you’ll only really know how all of the elements interact together once the car is out on track for real. The important thing for the race engineering department is to understand how to interpret that simulation information and, given its limitations, how to combine it with the real-world data, bringing it together to make the right decisions.