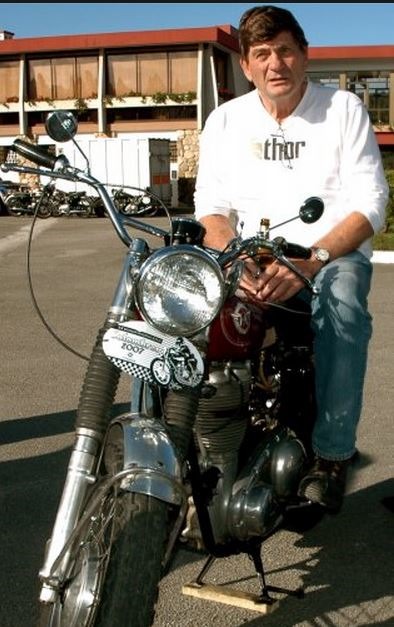

Drino Miller 1941 – 2014

|

| Drino Miller |

Drino Miller, whose successes in motor racing spanned the distance from Baja's off road races to professional sports car racing, and from the driver's seat to an engineer's drafting table, lost his final race, against cancer, on March 4th. Born on July 30, 1941, he was 72 years old.

In auto racing, legendary status is usually reserved for drivers, and a very few team owners. Los Angeles-area native Drino was only briefly a driver or team owner. Yet such were his accomplishments over four decades that racing insiders from all forms of motor racing acknowledge that he was indeed a legend. A racing renaissance man, Drino excelled as a driver, a team manager, a team owner, an engine builder, and an engine and chassis designer.

With a degree in political science from UCLA, Drino was well equipped for motor racing's notorious, byzantine politics, but was equally adept as a self- and experience-taught engineer.

That was immediately evident.

Drino's introduction to the sport grew out of the transition from the early, recreational dune buggies to cars which competed in the first endurance races held over the wilderness of the Baja Peninsula.

Drino served a sort of apprenticeship with Bruce Meyers, originator of the off-road Meyers Manx, which really began the dune buggy craze. In 1967, Drino was part of the Meyers team that produced a vehicle for Ed Pearlman, a San Fernando Valley florist, to attempt a record on the end-to-end Baja trek. Drino, fluent in Spanish and with Baja, was drafted to drive journalist John Lawlor, who provided press coverage.

The record did not fall, but the attempt led Vic Hickey, a General Motors R&D engineer, to hire Drino to develop a massive Baja race truck. When GM later passed on the project, Hickey convinced speed equipment baron George Hurst to underwrite the project, which became the Baja Brute.

Drino and Al Knapp drove the Brute in the first Mexican 1000, in October, 1967, but dropped out with broken suspension.

The experience led Drino to conclude that an anti-Brute – a lightweight, single-seat buggy – was the solution to Baja's challenge. Renting a garage, he designed and assembled his first car, and modified the VW-based engine. His $2,500 creation took second place in 1968's Mint 400, Mexican 1000 and Baja 500 races.

The following year, Drino set up shop with partner Stanford Havens, where they created the Baja Bug, a cut-down, hopped-up version of the Volkswagen Beetle. While selling parts and modifying Beetles, Drino also pursued improving his single-seat race car. He returned to Baja with it in 1970, co-driving with Vic Wilson. They dominated that year's Mexican 1000, winning in just over 16 hours, by a margin of over an hour, and beating the previous record by 11 and a half hours.

Collectively, those accomplishments led to his being inducted into the Off-Road Hall of Fame in 1978, its inaugural year, along with Meyers, Pearlman, and Hickey. It also set Drino on a life-long quest to advance technology in motor racing.

Soon the sole proprietor of what then became Drino Miller Enterprises; he continued to build off-road vehicles and engines, gradually expanding into doing engines and chassis development for racing sports cars and midgets.

In 1974, Drino partnered with Eddie Riddle to go midget racing. Roger Mears drove, all of them attempting to make the transition from off-road racing, where Mears had been very successful. It was a steep learning curve for all, though Drino's engines were already highly respected in the sport. While the car was fast, more often than not, the team's races ended abruptly with Mears crashed.

In 1975, Drino, running the team alone, put Danny McKnight in the car. Running mostly on the West Coast, they dominated for three years, winning the United States Racing Club championship in '77.

In 1978 and '79, Drino set his sights on the national USAC midget series, with Sleepy Tripp replacing McKnight. Together, they won a handful or races each year, and were always competitive for wins, but Tripp was handed a 30-day suspension by USAC for fighting in the pits in '79, which eliminated them from championship contention.

Drino then graduated to the Indianapolis 500, as crew chief for the Whittington Brothers team in 1982. The effort resulted in second- and third-row starts for, respectively, brothers Bill and Don. Less was achieved in '83, and in '84 Drino worked with the Interscope team and driver Danny Ongais, as team manager and crew chief. Ongais started the 500 from the middle of row four and finished ninth.

In 1985, Drino closed his shop, and began a five-year stint at Porsche racing specialist Andial. Over the years, Drino was involved as an engineer with the legendary Porsche 962, the racing version of the street 944, and eventually the 935, a racing version of the German marque's 911.

Andial's Alwin Springer, who became a life-long friend, tells a story which is typical of Drino's engineering prowess and the speed with which he could almost divine solutions to problems which eluded others.

When the first Andial-modified 935 was taken for its second pre-season test, the driver found the chassis flexing and the car undriveable. It was taken back to the Andial shop and stripped to the bone. Miller, not yet working at Andial, was recruited to look at the bare car. "He told us to add a few pieces of tubing to the chassis in certain places. We did, and it transformed the car," says Springer.

At Andial, Drino worked on racing engine modification and design, created engine and chassis parts, and worked on car design as well.

In 1989, Drino moved to Toyota Racing Development USA (TRD) as chief operating officer, managing both the race engine shop and the retail performance parts business. Initially, Drino was involved in supporting Dan Gurney's All American Racers (AAR) team as they transitioned from IMSA sedans to sports-racing prototypes.

The AAR operation was saddled with hand-me-down Toyota Le Mans endurance cars, which proved uncompetitive in IMSA sprint races against factory race cars produced by Nissan and Jaguar.

Gaining competitiveness required a new car and engine. AAR created the car, and Drino designed the engine, a 2.4-liter turbocharged four-cylinder, and was in charge of its creation, testing and development.

The combination of car – the Eagle Mk-III — and engine was introduced mid-season in 1991 at Laguna Seca, with Drino continuing to serve as team manager. The Mk-III won for the first time in the season-ending race at Del Mar, near San Diego.

The 1992 season saw two Mk-IIIs, in the hands of Juan Manuel Fangio II and P.J. Jones, supremely dominant over the second-generation cars from Nissan and Jaguar. The team breezed to wins in nine of the 13 races and the IMSA championship. The car was raced to the championship again in 1993, against modest competition. Drino's engine and AAR's race car had raised the bar beyond what Nissan and Jaguar were prepared to reach, both factory teams quietly disbanding at the end of the '92 season.

At the end of 1995, Drino and Toyota parted ways, with Drino joining Gurney's AAR operation. AAR returned to fielding cars in the open-wheel CART series, with engines and backing from Toyota. After four years of racing with little to show for it, Toyota pulled out, as did long-time Gurney supporter Goodyear, and the team withdrew from competition.

In 2000 Drino served as team manager and race engineer for a Formula Atlantic car, entered by AAR and driven by one of Gurney's sons, Alex. Drino also served as driving coach, as Gurney was beginning his career.

Drino joined Pro Circuit, a leading manufacturer and retailer specializing in motocross competition products, in 2003. When Drino signed on, motocross racing was transitioning from two-stroke to four-stroke engines. Drino was charged with developing a Kawasaki four-stroke for the series, and designed the complete valvetrain, including the camshaft, and was on an ongoing basis involved in developing all aspects of the engine as well as the transmission. The continuing success of Pro Circuit's in-house teams after four-strokes were adopted remains a testament to Drino's broad-based knowledge and expertise. Nearing retirement and his 70th year, Drino continued at Pro Circuit working a few days a week until his illness prevented that.

Drino is survived by his wife, Lisa. A celebration of life will take place at the Miller home on April 19th.

For more information and to send condolences to Lisa: lisaegustafson@sbcglobal.net