Remembering NASCAR’s J.D. McDuffie

|

||

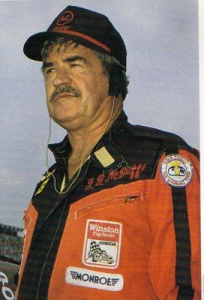

| J.D. McDuffie | ||

|

||

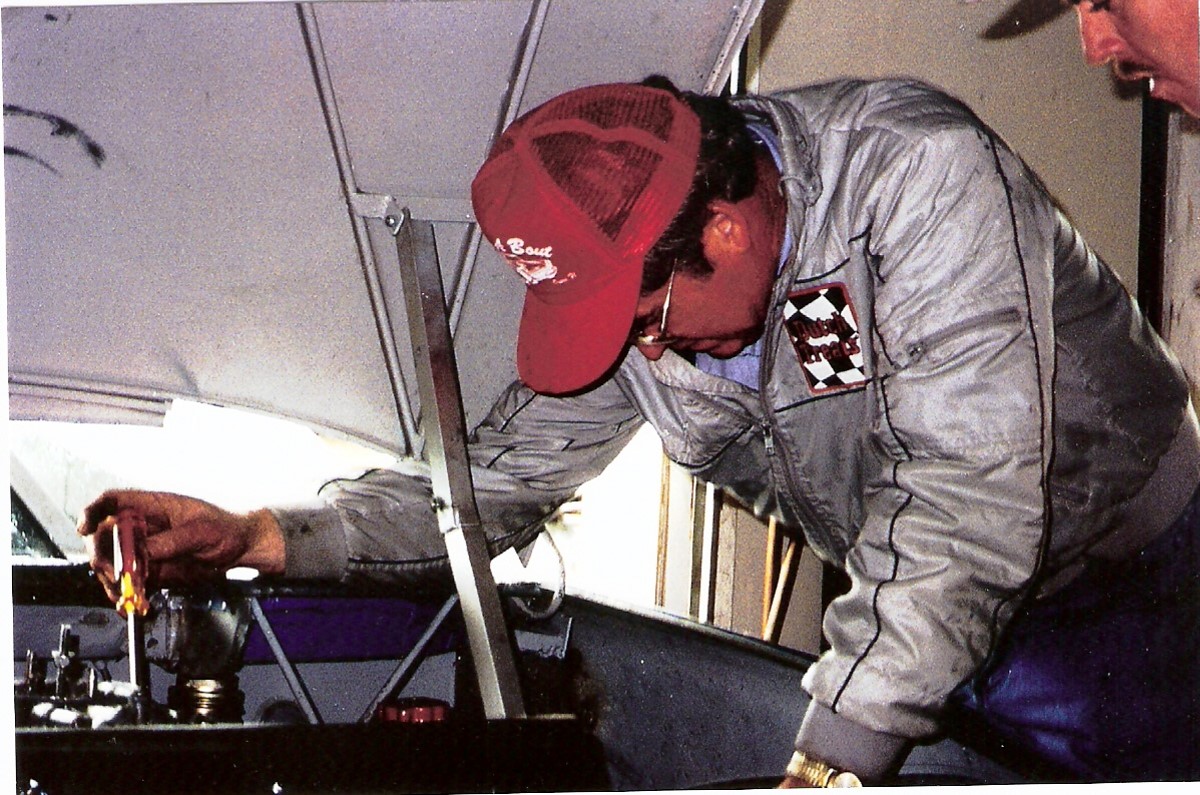

| J.D. working on his engine | ||

|

||

|

||

| J.D. posing with his favorite car at Daytona | ||

|

||

| McDuffie with his Mercury at Charlotte 1971 | ||

|

||

| J.D. McDuffie in his later years |

A stock car race in Winston-Salem, NC in 1949 is far removed from the bright lights of the modern NASCAR circuit. Doesn’t it follow that a driving career launched at that race would be just as different from today’s celebrity drivers?

A 10-year-old John Delphus McDuffie attended the Winston-Salem event with his Uncle Reuben and his brother Glen. They watched the legends of racing’s by-gone era compete for supremacy: Curtis Turner, Glen Wood, and Billy Myers. Glen McDuffie remembers Myers winning the race and J.D. not being around for the finish. Exhaust fumes had made J.D. ill and he was long gone when the checkered flag flew.

Nauseous or not, a fuse was lit within the boy from North Carolina’s sandhills. J.D. McDuffie had found what he wanted to do with his life. As he grew older, and attained the means, he and his father-in-law raided the junkyards and a race car emerged. McDuffie began racing on the local dirt tracks. He won races at small speedways across eastern North and South Carolina. By 1962 he was track champion at a dirt facility near Rockingham, NC. The success created a desire to hunt the big game: NASCAR’s Grand National circuit.

McDuffie took his first shot at NASCAR's big time on July 7, 1963 at Rambi Raceway in Myrtle Beach, SC. He drove a 1961 Ford, an old Curtis Turner car, with a refurbished role cage and a big “X" painted on the door. J.D. started 14th and finished an uneventful 12th in a race Ned Jarrett won. McDuffie earned $120 for his efforts. However, that event propelled J.D. McDuffie to 653 Grand National and Winston Cup starts over a 27 year career.

The victories J.D. experienced on the dusty ovals near home never materialized on NASCAR’s top circuit. A third place run at Albany-Sarasota Speedway in upstate New York in July of 1971, a race won by Richard Petty, would be J.D.'s best career finish.

Yet the fact that McDuffie never visited victory lane in a Winston Cup car doesn’t mean his racing career wasn't successful. J.D twice finished in the top 10 in driver points and won the pole for the 1978 Delaware 500, which earned him a spot in the inaugural Busch Clash at Daytona the following February. Despite the third-place run in New York in 1971, his best overall showing was arguably the 1979 Music City 420 in Nashville, TN. McDuffie qualified ninth and finished fifth while leading 111 laps, the most laps he would ever lead during a single race. But, and perhaps fittingly, his performance was a mere afterthought in the media.

Such media oversights were typical for the independent driver, and McDuffie personified the independent as well as anyone. Seldom did such men draw the wealthy sponsors or the fame and notoriety that racing held. But the lack of media attention was no indicator of the owner-driver’s talent, knowledge, and determination. J.D. possessed all three qualities, and they brought opportunities to drive faster, more durable cars for other team owners. One such offer would carry Benny Parsons to the 1973 Winston Cup championship. According to Glen McDuffie, J.D. declined the ride — fielded by L.G. DeWitt — twice. When Glen asked his brother why he shunned the opportunity J.D. responded, “I don’t want anybody telling me what to do."

The reply was vintage McDuffie. His resolve and dogged determination to make his own way earned J.D. a garage area respect that money couldn't buy. His attitude would win one of his greatest allies, a fellow North Carolinian known as the Intimidator.

Dale Earnhardt assisted J.D.’s lonely struggle several times, even donating the winnings from pre-race poker games to McDuffie Racing. Once when McDuffie’s only engine went sour prior to a Pocono race, he approached Earnhardt about borrowing an engine for the weekend. Dale obliged and J.D. raced on Sunday. Getting the engine wasn't nearly as difficult as returning it. Whenever J.D. mentioned the engine Dale would wave him off with a promise to get it later. J.D.’s wife Jean recalled a similar situation at Daytona.

J.D. was on the qualifying bubble, so Earnhardt passed the hat around the garage. The other teams contributed enough money to buy another engine for McDuffie Racing. Unfortunately, as Jean tells it, “That engine wasn’t any faster than the one J.D. had, so it wasn’t much help. But he appreciated the effort."

The admiration for J.D.’s determination and resilience wasn't limited to NASCAR's competitive inner circle. Jean remembers volunteers at every track who would pitch in with anything the number 70 car might need. “He never had to ask," she says.

The volunteers were numerous and time has caused their names and faces to fade into memory. But one man stands out in Jean McDuffie's mind, a man know simply as Big John. The man fit the moniker in both strength and stature, and he helped pit McDuffie’s car during California races. “I can still see him," Jean says, “walking through the garage with a mounted tire and wheel in each hand."

The help received from willing fans and other race teams was indispensible. But J.D. himself was McDuffie Racing's best and most dependable asset. McDuffie was an excellent mechanic and his knowledge of race cars might’ve made him another Richard Childress. Don Rumple — son of the late Tom Rumple, founder of McDuffie sponsor Rumple Furniture — witnessed J.D.’s expertise firsthand. “He was a great mechanic who would’ve made a good crew chief," says Don. “But J.D. liked to do his thing and was happiest behind the wheel."

An incident in the Daytona garage highlighted not only J.D.’s mechanical abilities but also the resourcefulness that helped him overcome the hardships common to his independent effort. Remember how your grandpa taught you to straighten a bent nail? Roll the nail slowly and tap it with a hammer until the shank is again true. Don Rumple witnessed J.D. using that principle on a much grander scale.

McDuffie had bent his car’s rear axle during a practice session. A wealthier team would’ve tossed the damaged part in the scrap heap. But waste wasn’t an option in the McDuffie Racing stable. When Don Rumple poked his head inside the garage stall there sat his driver gripping a borrowed torch. The bent axle lay over a couple of old tires and J.D. was heating the metal, rolling the axle and banging it with his hammer. Eventually, the axle was as straight as your grandfather’s nail and the McDuffie Pontiac raced on it that weekend.

Such resourcefulness was a necessity for J.D., and it indicates the mountains he conquered to remain a part of the Winston Cup Series. Racing was seldom easy for J.D. McDuffie and by the late 1980’s it was becoming even more difficult, if not downright impossible. NASCAR was changing rapidly. The independent drivers, like the dirt tracks NASCAR’s top level had once called home, were becoming musty relics in the corner of racing’s basement.

To complicate matters, J.D. suffered serious burns from a fiery crash during a qualifying race for the 1988 Daytona 500. Contact with another car sent J.D. into the outside wall, rupturing the oil cooler. Flames engulfed the driver's compartment as the car slid to a halt on the track’s apron. Fortunately, J.D. escaped the inferno under his own power. But he spent race day in a Daytona hospital with second and third degree burns, especially to his hands. The fire was so hot that it melted McDuffie's steering wheel. Even worse, someone had taken J.D.’s brand new pair of fireproof gloves from his driver’s seat the very morning of the 125-mile qualifier, gloves that would've prevented the burns. He raced anyway. Somewhere, someone had a racing souvenir. J.D. wore the scars.

During the Daytona 500 a few days later J.D. spoke to the television broadcast crew from his hospital room. “All I ever done is race, it’s all I know" he said. “I still love to do it and I’ll be back. This ain’t going to get me down."

J.D. raced only 17 times between 1988 and 1990. When he arrived at Watkins Glen, NY in August of 1991 McDuffie had made the field only four times in the season’s 17 races. But the night before the Budweiser at the Glen J.D. found triumph. He won an all-star race at the Shangri-La Speedway in Owego, NY. Less than 24-hours later, on August 11th, John Delphus McDuffie lay dead in the driver’s seat following a violent crash in the demanding Turn Five at Watkins Glen International.

Opinions vary on what caused the fateful accident. News accounts say the right front wheel broke loose, which is plainly evident in video of the wreck. Other observers claim contact with another car started the incident, or blame brake failure or a stuck accelerator. Whatever the cause, McDuffie died instantly of brain injuries after his Pontiac slammed into a tire barrier, flipped, and landed on its roof.

The L.C. Whitford Company of Wellsville, NY was J.D.’s sponsor for the Watkins Glen race. It was the company’s first and only experience in Winston Cup racing, a one-time deal made at the request of a Whitford employee who had previously worked on McDuffie’s pit crew. Company president Brad Whitford never had an opportunity to meet McDuffie and couldn't even attend the race. But, in a chilling twist of fate, Whitford turned on the television just in time to see a replay that “made me sick to my stomach."

It’s been said that a person’s worth isn't truly appreciated during their lifetime. J.D. received little recognition during his career, but the void he left when he died was clearly understood. “J.D. was just a humble man that everyone liked," said Tommy Bridges of the Bridges-Cameron Funeral Home, who conducted J.D.’s service. The sheer volume of mourners who paid tribute to Sanford’s favorite son was among the largest Bridges has witnessed during his 50 years in the field.

Race fans transformed Sanford, NC into an RV campground resembling Charlotte Motor Speedway's infield on race day. News crews rolled film. Winston Cup drivers and car owners — out of respect for their fallen competitor — spurned interview requests as they filled the Grace Chapel Church to overflowing. Hundreds more mourners stood in the churchyard. Outside interest was enormous, but it wasn’t the out-of-town fans or the racing celebrities that caught Don Rumple’s eye.

Rumple rode third in line behind J.D.’s hearse in the funeral procession. There was no fanfare. Instead an eerie silence hung over Sanford’s streets and businesses. It was as if the President of the United States was being laid to rest. “People were stopped, quiet and somber," Don recalls. “When J.D.’s hearse passed by all activity would cease. Sanford had lost one of its own and was mourning his passing."

J.D. McDuffie was a sports figure to race fans and something of an icon on the NASCAR circuit. To the people of Sanford he was far more than a hometown hero; he was their neighbor and their friend. He was a brother, a father and a husband. His on-track successes were modest, especially when measured against racing’s contemporary standard. Yet, in a way, J.D. McDuffie was more successful than NASCAR's brightest and wealthiest stars. J.D. never had to bow and scrape for the suits and ties of an image-conscious corporate sponsor. He never had to mince words nor pander to anyone.

J.D. was a racing man, his own man. He was a man of easy smile, a brushy mustache, and a thoroughly gnawed Tampa Nugget cigar. McDuffie maintained his independence and resourcefulness in a sport where both were destined for extinction. Along the way he earned respect from competitors who routinely defeated him on the track. He also won allegiance from fans who appreciated his struggle, silently hoping against all odds for NASCAR's Don Quixote to mount his stock car and topple the windmill.

J.D. raced a long, hard road against some of NASCAR's legendary figures. Yet he remained the same J.D. McDuffie whose dreams of racing glory began on a sultry summer night in Winston-Salem, NC. He was the regular guy down the street who just happened to earn a living at nearly 200 mph.