The Anatomy of the Andretti Curse at Indy

|

| The 1969 Indy 500 has been the lone Indy 500 win for an Andretti as a driver |

Pistons failed, spark plugs went bad, tires suddenly came loose, and valves suddenly lost pressure. There was a very noteworthy instance of USAC incompetence, a never before or since seen “Spin and Win," the first last lap pass in Indianapolis 500 history, and the curious yet still unsolved case of “That Damn Coogin." And more often than not, you were bound to find a calculating Unser, Roger Penske and sometimes an unholy alliance of the two behind the dirty deed.

Combined, it all adds up to Indy car racing's most famous and mysterious tale: the Andretti Curse.

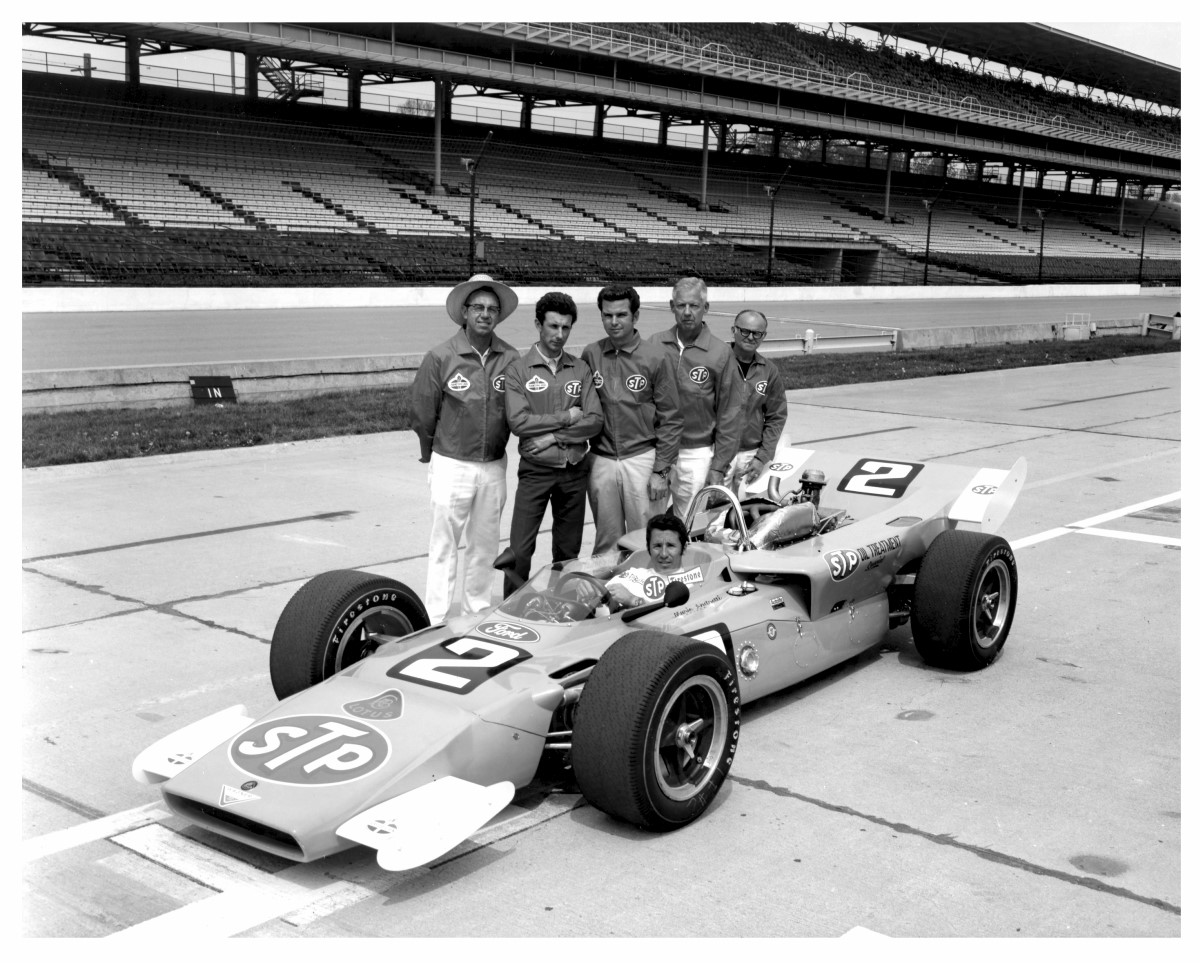

Ever since Andy Granatelli planted the famous victory smooch on Mario Andretti’s cheek in 1969, one of Indy car racing’s most renowned families has gone winless behind the wheel at the sport’s greatest cathedral. Sure, Michael Andretti won the Indianapolis 500 as an owner in 2005 and 2007. However, the Andretti Curse, which afflicted him and his famous father, and continues with his son Marco, remains alive and well.

|

| Even in 1969 Mario had bad luck – the Lotus he was driving dominated every practice session but a right rear broke sending the car into the wall. He had to qualify and start his backup car – the Brawner Hawk – which took him to victory |

Yes, multiple Andrettis can qualify up front, lead numerous laps, lap the field (multiple times even), take the lead in turn 1 from the sixth starting position, even lead lap 199. But the family hasn’t led lap 200 for 44 years despite coming astonishingly close on many occasions.

In fact, of the 33 races since 1980, an Andretti has led at least one lap an astonishing 18 times. This statistic becomes even more impressive when you consider no Andretti competed in 7 of those races. Six times during that stretch an Andretti has led the most laps, including each race in a three-year stretch from 1991-1993. If you include cousin John, multiple Andrettis managed to lead laps in 4 of those races. Incredibly, in 2006, both Michael Andretti and son Marco led the race with less than 5 laps remaining. Yet, the family has recorded zero wins behind the wheel aside from Mario’s 1969 triumph.

Of course, numerous people will simply say the family is destined to somehow find a way to not win The Greatest Spectacle in Racing. While I tend to be something of a cold rationalist, someone of the “you make your own luck" persuasion, even I cannot deny the Andrettis seem inexplicably snake bitten at Indy car racing’s most hallowed ground. While the outcome of this race or that race can be explained with ease, the fact the Andrettis have experienced so many near misses over the last four decades defies anything I can reasonably comprehend.

However, in studying the famed Andretti Curse, there are numerous themes that do emerge again and again with the famous’ family’s tale of woe. Call it "the Anatomy of the Andretti Curse," as we explore some of the recurring themes that comprise Indy car racing's most storied tale.

|

| In his 2nd and 3rd starts, Mario was on pole for the 1966 and 1967 Indy 500, only to drop out early |

1. Mario drops out of the 500 incredibly early, due to a crash or inexplicable mechanical failure, perpetuating the “what should have been questions:" 1966, 1967, 1968, 1971, 1973, 1982, 1986, and 1994

Mario Andretti finished the Indianapolis 500 30th or worse, seven times. His early exits from races, often exacerbated the legend of the Curse, as people forever wondered “what could have been." For example, you'll hear "Mario started from pole that year, and would have easily won."

Now, to be fair it is unlikely Mario would have seriously competed in a few of those races. For example, 1994 was the year of the Penske pushrod Mercedes, and Mario's final start at Indy. However, aside from the 1986 race, Andretti started each race listed above in the top-10, and from pole in 1967.

Clearly, it would be hard to reasonably hypothesize what exactly would have happened. Still, Mario wasted numerous solid qualifying efforts with incredibly early exits, only adding to the mystery of what might have been.

2. Mario charges early but has to make a pit stop to fix something inexplicably wrong with the car. He loses many laps, is not a factor in the outcome, but shows significant speed, again prompting more “what should have been," questions: 1970 and 1978

In 1970, Andretti started ninth, but was forced to pit early after body-work inexplicably came loose on his car.

That year, Al Unser would capture his first of four Indy 500 victories.

The 1978 race is of particular interest as Andretti started that year’s race 33rd. Driving for Penske, he was forced to start at the back as he could not qualify his car due to a Formula One conflict.

Moving up 20 positions in the early going, Andretti was looking as if he could be the first driver to win after starting last. However, he is forced to pit to have his spark plugs changed. He would lose 8 laps, and not contend for the victory.

That year, Al Unser would win his third Indianapolis 500.

In each of these instances, Mario had incredibly fast race cars, yet mechanical gremlins prevented him from contending. And again, we are left to wonder what might have been.

3. An Andretti dominates most of the race, before falling victim to mechanical misfortune. Instead of an Andretti earning a deserved victory, a cool, calculating, and fortunate Unser wins again: 1987, and 1992

If the Andrettis are Indy’s hard-luck family, the Unsers are the race’s trust-fund kids. Yes, the Unsers have combined to lead more total laps 1,194-1,079, but not by a large margin. Certainly, such a margin would not forecast an 8-1 wins margin.

Still, whether the Unsers are deserving of their spoils relative to the Andrettis does not change the simple fact: Unsers have won 8 Indy 500s, whereas the Andrettis have won only one. Notoriously more calculating, easier on equipment, the Unsers were around at the end of the races more often.

In fact, Al Unser, was running at the finish of 18 Indy 500s. By comparison, Mario Andretti was running at the end of a mere five Indy 500s.

|

| In this Lola engineered by the great Adrian Newey, Mario dominated the 1987 Indy 500 like no driver had ever dominated it before. Then with 13 laps to go his American bucket of bolts Chevy engine broke. |

One such example was in 1987 when Mario Andretti started from pole, led 170 of the first 177 laps, and was more than a lap ahead of 2ndplace Robert Guerrero when his ignition surprise, surprise, failed. Guerrero would inherit the lead before surrendering it to longtime Andretti nemesis Al Unser when stalling on his final pit stop. Unser would go on to capture his fourth win.

Another example of Unsers celebrating at the hands of the unfortunate Andrettis occurred with the second-generation stars Michael Andretti and Al Unser, Jr. in 1992.

Michael dominated the entire afternoon leading 160 laps before losing fuel pressure on lap 189. This, of course, while Mario and Michael’s brother Jeff were both at Methodist Hospital recovering from crashes earlier in the running. Al Unser, Jr. would inherit the lead from Michael and score his first of two victories. Although Unser, Jr. was one of the sport’s best at the time, and the Indy car world had grown familiar with cool, calculating Unsers celebrating at the hands of hard-luck, dominant Andrettis, the outcome that day seemed unjust, and beyond cruel.

4. An Andretti brings the car home, but falls victim to USAC incompetence, and the unholy Penske/Unser Alliance: 1981

Of course, 1987 saw a Penske/Unser alliance cruelly defeat the Andrettis, as well.

However, 1981 was the year of the famous USAC decision, in which, Unser was initially declared the winner. The very next day Andretti was named the winner, yet that decision was overturned months later as Unser was restored the victory.

5. If it’s not a joint Penske/Unser effort, an Unser solo act or inexplicable mechanical gremlin, then it’s a Penske solo act:, 1985, 1991, 1993, 2001 and 2006

Sadly, it didn’t matter who was piloting the Penske machines (if you include 1891 and 1987 with the years above, there were six different drivers.) And each time an Andretti was left to wonder what might have been.

Of course, I briefly mentioned 2006 earlier, when Marco Andretti was passed coming to the checkered flag by team Penske’s Sam Hornish. For now, let’s talk about 1985.

|

| Danny Sullivan spins in front of Mario then wins in 1985 |

Mario Andretti led a race high 107 laps and seemed to be on point headed into the race’s second-half. However, on lap 120 Team Penske’s Danny Sullivan charged past Andretti in turn 1, before an incredible 360 degree spin in the short chute.

Miraculously, Sullivan kept control of the car, and drove on, ultimately passing Andretti on lap 140. Sullivan never looked back, winning his first and only Indy 500.

|

| 1991 – Michael Andretti passes Mears on the outside in Turn 1 and Mears returns the favor a lap later |

In 1991, Michael Andretti led the most laps, but fell victim to a miraculous outside pass by Rick Mears going into turn one. Mario Andretti led the most laps in 1993, but fell to fifth after a late race pit miscue. Penske’s Emerson Fittipaldi won that one.

6. On the rare occasion, Penske can't beat the Andrettis straight up, he does so through an auxiliary: 1989

In 1989, Michael Andretti passed Fittipaldi on lap 154. By that point in the race, Andretti, Fittipaldi and Unser, Jr. appeared to separate themselves from the rest of the field. Sadly, or perhaps predictably, Andretti’s engine would expire 8 laps later.

Of course, people will point out that Fittipaldi was driving for pat Patrick’s team in 1989. But remember, Fittipaldi used the Penske PC-18 chassis.

2001 saw Michael Andretti return to Indy after a five-year absence due to the CART-IRL civil war. He would finish third in the race, leading during the middle part.

Of course, Penske, this time with Helio Castroneves and Gil de Ferran posting a 1-2 finish defeated Michael.

7. On the rare occasion a Penske doesn't win, and the even rarer occasion a Penske driver self-implodes, Penske still manages to screw the Andrettis: 1982

While Roger Penske never messes up, his drivers occasionally do.

Perhaps, the most memorable instance of a rare Penske foul-up occurred at the start of the 1982 race. Penske teammates Rick Mears and Kevin Cogan started one-two with A.J. Foyt third and Mario Andretti fourth.

Coming to the green flag, Cogan’s car suddenly snapped right hitting Foyt, then ramming into Andretti on the inside. “That Damn Coogin," as Foyt referred to the unfortunate Cogan, who had just taken out two less than forgiving Indy car legends, was never the same, and fired by Penske at the end of the season.

Foyt was able to restart, while Andretti joined Cogan, Don Whittington, and Roger Mears out of the race.

While we’ll never know how Andretti’s race may have turned out, it is worth noting his Patrick Racing teammate Gordon Johncock won the race. However, in the irony of all ironies, on the rare occasion a Penske driver makes an unexplainable error, it costs an Andretti.

Overall, the Andretti Curse has taken on a life of its own. Beginning with a young Mario Andretti falling victim to mechanical gremlins, it continued as a fast Andretti failed to add to his win total in the 1970s and 1980s.

When Michael appeared on the scene in the mid-1980s, he was a contender on numerous occasions. Leading the most laps twice, and falling victim to mechanical gremlins, as well, Michael miraculously seemed to simply inherit the same luck as his father.

|

| As if he had Nitrous Oxide, Sam Hornish blew past Marco Andretti like he was standing still to win the 2006 Indy 500 by a car length |

Of course, The Curse lives on with son Michael's son Marco. Marco, seemingly had the his first Indy 500 in 2006 won, before Team Penske's Sam Hornish miraculously darted past him coming to the checkered flag. Marco noted at the time, that he had no idea where on earth Hornish's sudden burst of speed came from.

And we may never know what exactly powered Hornish past Andretti in that amazing finish. However, suggesting the Andretti Curse may have played something of a role, might not be all that preposterous.