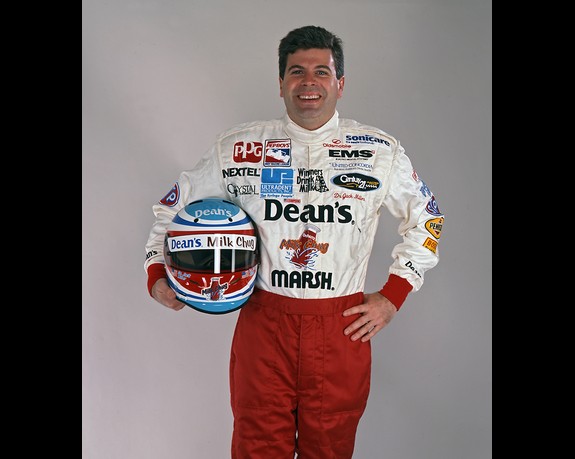

Remembering Dr. Jack Miller, the Racing Dentist

|

| Dr. Jack Miller Indy 500 Photo |

Stephen Cox is on vacation; this week's article is a re-release of a popular article from 2012.

Twelve years ago, Dr. Jack Miller and I sat down for lunch at a crowded restaurant on the west side of Indianapolis, just minutes from the world famous 2½ mile oval. Jack seemed to be in a good mood.

Although we had spoken several times at the Speedway, we were really just passing acquaintances. I had suggested we have lunch so I could ask about his business deals and get a fresh perspective on how an ordinary guy gets to the Indy 500. There was no marketing agency, personal assistant or PR rep involved. I just called him up and asked. His response was cheerful and positive.

Jack ordered a hamburger and fries and began explaining that he had no intention of going into immediate, full-time dental work. His goal was to become a race driver. Dentistry was to be his second career later in life.

|

| Dr. Jack Miller in his office |

He hadn’t hired a marketing firm to craft his racing career. Instead, he had put together every sponsor deal himself with hundreds of phone calls while wading through one rejected proposal after another. He soon became known for throwing samples of toothpaste into the grandstands, and his Crest-sponsored machine was one of the most recognizable cars in the series.

Jack Miller intrigued me. Here was a man who had taken more public criticism than anyone I’d ever known. The criticism leveled against him by several journalists was more accurately classified as defamation of character or libel.

Miller drove Indy Lights in 1993, where he won a B Series championship title against a modest field of competitors. One particularly spiteful journalist asked how Jack Miller could “have the gall" to stand on the podium to accept his award when so few cars were entered in the B series?

Well, there was a simple answer that any journalist worth the name should have found.

In 1993, the Indy Lights series had just switched from the old March chassis to a new Lola chassis. Series officials chose to run the Lola teams in a separate division because of the significant difference in performance between the two cars.

Miller’s ride happened to be a March chassis. He entered the division that was created for his machine. Of course, Miller had no control over how many cars were in the B series field. He just showed up, did his job and won the title.

That information was available to anyone who cared to look, but no one bothered.

|

| Dr. Jack Miller throwing Crest toothpaste samples into the crowd at Indy |

Miller raced Indycars from 1997 through 2001. After being mercilessly slandered in his hometown Indianapolis newspaper for two years, other writers began to mimic the paper’s petty malice. Miller was dubbed “The Racing Cavity," “the biggest joke we ever saw," and “another good marketer who couldn’t drive a greasy stick up a dog’s —." Once the newspaper’s accusations went viral, people who had never even met Jack Miller were writing unspeakable things about him.

Monkey see, monkey do. If Possession of Original Thought were a felony, few journalists would ever stand trial.

Jack finished off his French fries, pushed his plate back, and looked at me with an inquiring gaze. He said, “I don’t understand why they’re coming after me. I’m a local guy who started with nothing, and I’m chasing my dream. Why am I not considered an underdog that people want to pull for? What have I done wrong?"

|

| Dr. Jack Miller Diecast |

Jack was a good businessman who achieved his dreams by giving sponsors a solid return on their investment through public relations, good advertising, and hard work.

And ultimately, that was Jack Miller’s unforgivable sin.

He was portrayed as a guy who didn’t “earn" his ride through sheer talent, a long-extinct fantasy that rarely occurred at all. He was portrayed as a guy who got his ride because he was able to raise sponsorship through good business transactions, as if that were somehow circumventing God’s plan.

Before we finished lunch, Jack leaned across the table and told me, “Stephen, I have three photos hanging on my office wall showing me and my car at the start/finish line of the Indianapolis Motor Speedway. They can write anything they want, but they can never take that away."

A few weeks later I interviewed Jack on pit road for ABC television on Carburetion Day at Indianapolis. That’s the last time I ever spoke to him.

Although Miller never won an IndyCar race, he was, in fact, good enough to get there. He was good enough to qualify the only Infiniti engine in the field outside Row 5 at the 1998 Indy 500 against 32 vastly superior Oldsmobile entries.

Miller later scored a top ten finish at Charlotte. He would have started on the front row at Indy the following year had his engine not blown up on the final qualifying lap. That’s not bad for a guy who had somewhere near seventeen engine failures in two seasons.

Those who single out Miller as somehow being “spectacularly bad" demonstrate a shocking ignorance of what IndyCar racing was really like in the IRL era.

I am not suggesting that Jack Miller was an all-time IndyCar legend, nor do I believe that Jack would suggest that himself. But I did find him to be a humble, hard-working guy whose best moments in the cockpit were unjustly ignored.

Today, Jack owns three successful dental clinics in Indianapolis. He is a family man with a wife and two kids. He is an accomplished public speaker. He has organized his own construction and real estate development company.

And he made it to the Indianapolis 500, which is more than 99.9% of racing drivers – or journalists – will ever accomplish.

Maybe it’s time to give the man his due.