Tony Gaze dies at 93

|

| Tony Gaze |

Tony Gaze has died in Geelong, Victoria, at the age of 93. he was Australia’s first Grand Prix driver and a man with an extraordinary life. Below is an article about him in GP+, earlier this year. It is interesting to add that Tony is the step-grandfather of Will and Alex Davison, Australian V8 Supercar Drivers as well as James Davison, who is making his INDYCAR debut at Mid-Ohio this weekend.

Tony Gaze has led what can only be described as a charmed life. Now 92 years of age, he is one of the last surviving Royal Air Force fighter pilots of World War II; not to mention one of the few remaining Grand Prix drivers from the early 1950s.

Gaze is an Australian from British roots. His grandfather Thomas Gaze was an Englishman, born in Norwich in around 1862. He worked in the thriving local shoemaking industry before deciding to move to Australia. He settled in Perth, in Western Australia, and became a partner in a young shoe firm called the Ezywalkin Shoe Company. He married and had a family. His son Irvine moved to Melbourne and a new shoe company called the Clifton Shoe Company was established in the north-eastern suburbs of the city.

At 24 years of age, Irvine went to the docks one day in 1914 to see his cousin off. The Reverend Arnold Spencer Smith was a member of Ernest Shackleton’s adventurous Imperial Trans-Antarctic Expedition and was going to be the chaplain/photographer. At the last minute, the team found themselves a man short and Spencer Smith asked Gaze if he might join them. They set off to Antarctica in a ship called the Aurora and duly set up camp in the base that Robert Falcon Scott’s party had established a few years earlier.

Their job was to go inland and establish depots for the main expedition to visit after they had passed the South Pole and this was successfully done, however, the Aurora broke loose and drifted away and, in consequence, the team spent two years, living on the leftover supplies of Scott’s expedition, seal meat and penguin eggs. Spencer Smith died, but the rest of the party was finally rescued.

By the time all this had happened it was 1917 and Gaze wanted to do his bit for the Empire and so Shackleton organized for him to go to England where Gaze joined the Royal Flying Corps that summer, being posted to the elite No 48 Squadron. He was shot down over France in the last week of the war, and was entertained by his German counterparts, impressed by his Antarctic Medal. He was then sent off to a prison camp. He returned to England after the war was over and was posted to Tangmere, not far from Chichester. While he was there he met Freda Sadler, a driver with the WAAF. The two married in the UK in the spring of 1919 and later that summer sailed way to Melbourne, where they settled down in the shoe trade and brought up Tony, who was born in February 1920. He was followed by Irvine Jr, who soon became known as Scott, at the start of 1922.

|

| Tony Gaze |

The two brothers attended Geelong Grammar School and then went to England to study at Queens College, Cambridge. They had only been in England for a short time when World War II began. The two young men enlisted in the Royal Air Force, their goal being to follow in their father’s footsteps and become fighter pilots. They graduated from No 5 Flying Training School at RAF Sealand, near Chester, in January 1941 and then spent a short period with the 57 Operational Training Unit at nearby RAF Hawarden, learning about aerial combat. They were then posted to 610 (County of Chester) Squadron of the Royal Auxiliary Air Force, stationed at RAF Westhampnett, an airfield better known today as Goodwood. This was a satellite base of Tangmere. The squadron was at that point preparing to become part of Wing Commander Douglas Bader’s celebrated “Tangmere Wing", taking the fight to the Germans.

Back in Australia, their father was also serving with the Royal Australian Air Force, as a Squadron Leader, in command of the RAAF Training School at Essendon.

Sadly, just a few weeks after they joined 610 Squadron, Scott was killed in a flying accident, at the age of only 19. It was a terrible blow for Tony, but there was little time to mourn as the squadron was in constant action and that summer he shot down his first enemy aircraft and was awarded the Distinguished Flying Cross (DFC). He stayed with the squadron until November when he was posted to an operational training unit for a break, before beginning a second tour of duty in June 1942, as a flight commander with No 616 Squadron.

Two months later he was promoted to Squadron Leader with No 64 Squadron, but at the end of September he was leading a wing of Spitfires on bomber escort duty to Morlaix in France. The pilots had been told to anticipate a little cloud and a moderate headwinds. When they were over the Channel they discovered heavy cloud cover and, unknown to them, 100mph tailwinds, which blew them a long way south of the rendezvous point. They lost radio contact with England and turned for home, with fuel running low. On the way back one of the pilots of an American RAF squadron spotted a port below and thinking it was in England, they went through the clouds above the French port of Brest. Ten planes were shot down, one crashed on the way back to the UK and the 12th crash-landed on arrival. Although Gaze ordered the other two squadrons not to descend, he was blamed for the incident, although the official inquiry concluded that the incident was largely the fault of the weather and inexperienced pilots.

He returned to No 616 Squadron as a flight commander, until the end of his second tour of duty, during which he was awarded a second DFC, before spending a few months at the Air Ministry. He then returned to flying as a squadron commander and then after a brief period as an instructor, was back in the thick of it, flying from RAF Kenley with No 66 Squadron. On September 4 1943 he was shot down over Le Treport, parachuted out and managed to avoid capture and made contact with local resistant’s, who helped him to make contact with one of the escape lines and he turned up a few weeks later in the British Consulate in Barcelona.

He was transferred from there to Gibraltar and flew home in a Dakota. For the next few months he served with the Air Fighting Development Unit at Wittering, developing new techniques and testing captured enemy aircraft. He then went back into a fighter role and is credited with being the first allied airman to land on European soil on June 10 1944, when he and led a number a unit into an airfield at St Croix-Sur-Mer, near Bayeux, just four days after the D-Day landings. He continued as a fighter pilot as the Allied armies fought their way across France and over the Rhine and in February 1945 he shot down a Messerschmidt Me262 jet, which resulted in a third DFC. He also shared the destruction of an Arado AR234 jet. He was posted to 616 Squadron and then became the first Australian to fly the new Meteor III jet operationally. During the last days of the war, he had a strange experience when he landed his Meteor on a stretch of autobahn where Me262s were stationed and the pilots looked over their respective aircraft before Gaze flew back to base. He finished the war with 11 kills, three shares kills and four probable. He also shot down one V1 rocket.

And he was still only 25 when the war ended. During that period he got to know Kay Wakefield, the 30-year-old widow of Johnny Wakefield, a successful pre-war English racing driver who had been killed while flying in 1942, with the Fleet Air Arm. She had been involved in racing circles before the war and inevitably Gaze was drawn into that world. In 1946, in conversation with the Duke of Richmond and Gordon – better known in the motor racing world as Freddy March – Gaze suggested that the perimeter roads of the Westhampnett aerodrome – which was built on land belonging to the Duke – would make a very good racing circuit. As a result of that conversation March ran a car around the airfield, concluded that Gaze was absolutely right and in 1948 opened what is now known as Goodwood.

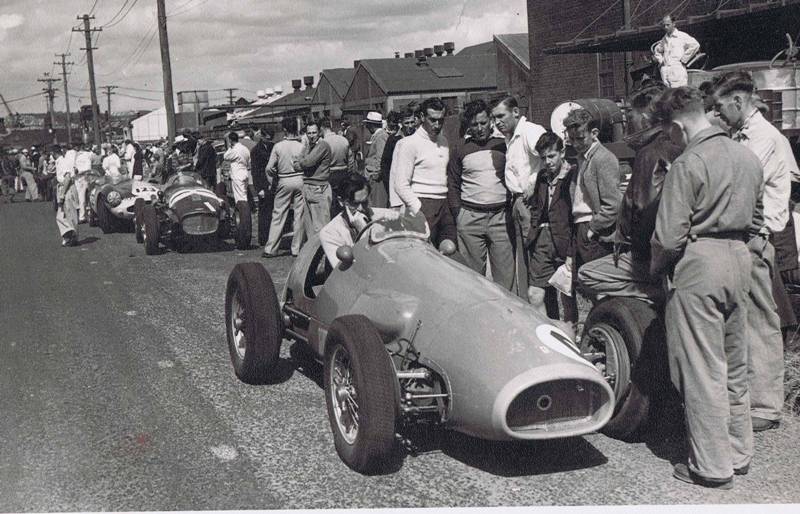

Once he was demobilized Gaze went home to Australia, taking with him a pre-war Alta racing car, with which he began his racing career on the Rob Roy hillclimb, near Melbourne (above). He remained in contact with Kay and she visited Australia. When she returned for a second trip in 1949 the two were married in Melbourne and then set off back to England, where they settled at Caradoc Court, a Jacobean manor house with extensive estates and stables, overlooking the River Wye in Herefordshire, which she had inherited from her father Colonel George Heywood. Gaze bought an Alta Formula 2 car for 1951, which he raced at various events all over Europe.

In an effort to get better results he switched to an HWM-Alta in 1952 and planned to once again race in Formula 2 races. At the last minute it was decided to run the World Championship to F2 regulations, as Ferrari was the only competitive team in Formula 1, following the withdrawal of Alfa Romeo. Gaze took part in a series of non-championship F1 events and then in June travelled to Spa to race in the Belgian GP . This was followed by appearances at the British and German GPs in July and August, although he failed to qualify for the Italian GP at Monza. He also raced a Maserati 8CM in various events.

The following year he became one of the first Australian crew to attempt the Monte Carlo Rally in a Holden FX with team-mates Lex Davison and Stan Jones, both well known figures in the sport in Australia. He had known Davison since the Rob Roy hillclimb days. The trio started in Glasgow and at one point even managed to get into the top 10 but ended up 64th on arrival in Monte Carlo. That year he raced an Aston Martin DB3 in sports car events and was fortunate to survive a crash in the Portugal Grand Prix when he was hit by a Ferrari and shoved into a tree. Luckily he was thrown out of the car in impact as the Aston landed upside-down and caught fire. Spectators rushed on to the track and carried Gaze to safety, his only injuries being cuts and bruises.

He next acquired an ex-Ascari Ferrari 500 F2 car, which he raced in non-championship events in Europe and then took to Australia and New Zealand in order to race in the winter events in 1954 and 1955.

Early in 1955 he returned to Europe and set up a team the first international racing team to fly the Australian flag. This was known as the Kangaroo Stable and ran Aston Martin sports cars for a number of young Australians, who were by then in Europe, trying to break into international racing, including a young Jack Brabham.

The Le Mans disaster that summer resulted in many races being cancelled and the Stable was forced to close down at the end of the year.

He continued to race, running second to Stirling Moss in the 1956 New Zealand Grand Prix

Tony would continue to race sports cars in the late 1950s, but later tried his hand at gliding, after a conversation with Prince Bira of Thailand, who was an avid glider competitor. He was an active member of the Bristol and Gloucestershire Gliding Club, at Nympsfield and went on to represent Australia in the World Gliding Championship, which was held that year at the Butzweiler airfield, near Cologne, in Germany.

He continued to have close links with the sport, notably with Davison, who had returned to Australia after the Monte Carlo Rally in 1953 and in 1954 won the first of four victories in the Australian GP, following up with wins in 1957, 1958 and 1961. In addition he had won the Australian Drivers’ Championship in 1957. He had even competed at Le Mans in 1961, in an Aston Martin with Bib Stilwell. His wife Diana was a racer as well, competing in hillclimbs, with an Alfa Romeo and an MG.

Lex was killed in February 1965 while testing a Brabham Tasman car at Sandown Park in Melbourne, but Tony and Kay kept in contact with his widow Diana in the years that followed.

Kay died in 1976, at the age of only 61, and Tony then decided to return to Australia, selling Caradoc Court, which has since become a hotel.

He and Diana spent decided to marry a year later.

By then Diana’s sons – John, Chris and Richard – were all involved in the racing world in Australia and in time they would produce a new generation of Davisons, notably Will, Alex and James, who are all involved in the sport, Will and Alex as drivers in the V8 Supercar Series.

Tony and Diana were regulars at historic events and in 2006, his contribution to Australian motor racing was recognized with the award of the Order of Australia.

Diana died last year at 86.