IndyCar could be forced to cancel 2016 Boston GP (4th Update)

04/23/16 A spokesman for the race organizers said in a statement that they plan to appeal the commission’s decision to the state Department of Environmental Protection.

"Recent amendments to the FEMA Flood Maps in March 2016 placed significant new areas in the city of Boston within the flood zone for the 100-year storm event," said Harry-Jacques Pierre. “Preparation for [the race] requires minimal work in the new flood zone."

In AR1.com's opinion, rather than appealing they had better have an engineering firm prepare the permit and get it submitted as an emergency request. A lot of money is at stake. Normally money would not be a reason the Corp of Engineers would grant a quick decision, but they can plead their case and hope for the best.

04/22/16 Boston Mayor Martin J. Walsh said Friday that despite environmental concerns raised by the Boston Conservation Commission, he was optimistic that IndyCar race organizers would be able to bring the event to Boston in September.

"I’m hoping to see it here Labor Day weekend," Walsh said to reporters at a public event Friday morning. “I think there’s a process now they can follow, and I think they have to follow that process and make their case."

Walsh said the commission was simply following environmental regulations, and race organizers would have to follow the process, no matter how inconvenient.

"The rules are there for a reason," he said. “You have to live by the rules and work by the rules. Clearly, if this was a year ago, it’s very different math. But unfortunately for IndyCar right now, they have to come up with how they are going to move forward."

The promoters’ attorney, Lauren Liss, warned that if the commission forced them to go through the wetlands approval process, it could potentially force cancellation of the race if opponents appealed any new permits.

Even if there were no appeals, the added time needed to get another permit would put promoters on a "very tight" construction schedule because they need to start putting shovels in the ground by June, Liss said.

Meanwhile….the clock is ticking and time is running out.

04/22/16

|

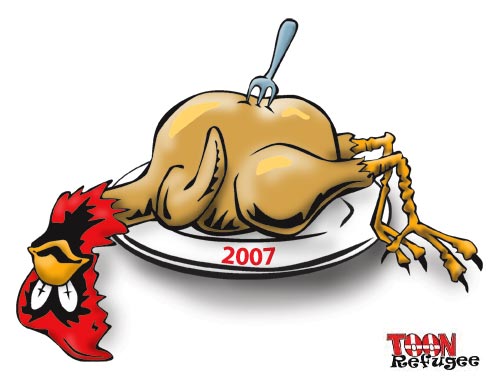

| If organizers are not granted a waiver for the wetlands permit, you can stick a fork in this year's race, it's done. |

The Boston Grand Prix, which is set for later this year, is facing new opposition. The IndyCar race is scheduled to hit the streets of Boston on Labor Day weekend. But the city's conservation commission could throw a wrench into those plans.

They're leaning on new climate change rules that would force organizers to get a wetlands permit. Part of the race course would require building in a flood zone.

Race organizers say getting the permit might cause delays that would force them to scrap the race, so they plan to appeal. If they lose the appeal the race will have to be scrapped. It takes six months to do all the construction for the event and we are already inside that window. And they have not even applied for the wetlands permit with the Corp of Engineers. On average, individual permit decisions are made within two to three months from receipt of a complete application. In emergencies, decisions can be made in a matter of hours. We doubt this is deemed an emergency, but we shall see.

They also say the timing isn't fair since FEMA only named parts of the seaport a flood zone six months ago, and the designation went into effect in March.

Commission members say the Grand Prix is a victim of its own poor planning.

Wetlands Permit Process – Is Onerous

Although there are numerous federal and state laws that affect wetlands, the Clean Water Act (CWA) is the main regulatory tool. There are two sections of the CWA that are of particular significance:

Section 404 of the Clean Water Act enables the Army Corps of Engineers (Corps) to grant permits for certain activities within waterways and wetlands. Construction projects affecting wetlands in any state cannot proceed until a §404 permit has been issued. In deciding whether to grant or deny a permit, the Corps must follow certain guidelines, which are discussed below.

Section 401 of the Clean Water Act gives EPA the authority to prohibit an activity, including a construction project, if it can impact water quality or have other unacceptable environmental consequences. For most states, EPA has delegated this authority to state environmental agencies.

These two regulatory activities are usually conducted cooperatively through use of a joint application form. The Army Corps of Engineers reviews permit applications to determine if practical alternatives to the project exist. They also impose mitigation requirements on the developer and perform a public interest review. The Corps also determines if other environmental laws must be addressed, including the National Environmental Policy Act, Endangered Species Act, and the National Historic Preservation Act. If the Corps' review reveals that the project should not proceed, they have the authority to either deny or condition the project. Then, using their §401 authority, state agencies review the permit application, looking closely at potential water quality impacts. When warranted, the states grant "§401 certification," which is needed before a §404 permit can be issued by the Corps.

|

| Will the tree huggers win again for something as stupid as this? |

Does My Proposed Project Require a §404 Permit?

To answer this question you need to know the definition of a wetland and understand what constitutes a regulated construction activity.

From a federal standpoint (state definitions may vary), the term wetlands means those areas that are inundated or saturated by surface or ground water at a frequency and duration sufficient to support, and that under normal conditions do support, a prevalence of vegetation typically adapted for life in saturated soil conditions. Wetlands generally include swamps, marshes, bogs, and similar areas. To help add consistency to the process of determining if an area qualifies as a wetland and to delineate its boundaries, the Corps of Engineers published the Federal Manual for Identifying and Delineating Jurisdictional Wetlands. There are two versions of this manual, the 1987 edition and the 1989 edition. Due to some political maneuvering (an explanation is beyond the scope of this web page), the 1987 version is the one that is used by the Corps.

The kinds of activities regulated under §404 of the CWA have expanded over the past 30 years, due mostly to changes in definitions of the terms found in the laws. Initially, regulated activities were limited to dredging operations and the "discharge of dredged materials" into waters of the U.S. It is important to mention this because, the law still limits the Corps authority to "waters of the U.S." and "discharge of dredged materials," but the interpretation of these terms has changed.

Waters of the U.S. are defined in 33 CFR Part 238. This definition is very broad and encompassing and includes lakes, rivers, streams (including intermittent streams), mudflats, sandflats, wetlands, sloughs, prairie potholes, wet meadows, playa lakes, or natural ponds.

The definition of "discharge of dredged materials" was significantly expanded in the 1990's and clarified in 2001 to include any addition, including any redeposit of dredged material into waters of the U.S., which is incidental to any activity including mechanized land clearing, ditching, channelization or other excavation. Importantly, this revised definition prohibits the incidental fallback of a material during removal activities without a permit, unless the material falls back to substantially the same place as the initial removal.

In essence, it is difficult to avoid the permit process for any kind of construction activity within a wetland.

Applying for a §404 Permit.

The Corps of Engineers issues two types of §404 permits applicable to the construction industry, general permits and individual permits. It is advisable that you contact the Corps and your state environmental agency prior to submitting a §404 permit application form. The Corps will make a determination as to which permit, if any, will be required. The Corps may choose to make a site visit before making this determination. Each type of §404 permit is discussed below.

Once a complete application is received, the formal review process begins. Corps districts operate under a project manager system, where one individual is responsible for handling an application from receipt to final decision. The project manager prepares a public notice, evaluates the impacts of the project and all comments received, negotiates necessary modifications of the project if required, and drafts or oversees drafting of appropriate documentation to support a recommended permit decision. The permit decision document includes a discussion of the environmental impacts of the project, the findings of the public interest review process, and any special evaluation required by the type of proposed activity.

Types of Permits.

There are two types of Section 404 permits issued by the Corps of Engineers, individual and general permits. The applicability of each type is described below.

Individual Permits. Activities in wetlands that involve more than minimal impacts require an individual permits. Most individual permits are issued through a process (see diagram), which begins with a permit application to a Corps office. Once a permit application is submitted, the Corps must notify the applicant of any deficiencies in the application within 15 days. After the applicant has supplied all required information the Corps will determine if the application is complete. Within 15 days of that determination, the Corps is required to issue a public notice of the application for posting at governmental offices, facilities near the proposed project site, and other appropriate sites. In the public notice, the Corps requires that any comments be provided within a specified period of time, usually 30 days.

The following is a summary of the typical processing procedure for a standard individual permit:

- Pre-application consultation (optional)

- Applicant submits ENG Form 4345 to district regulatory office.

- Application received and assigned identification number.

- Public notice issued (within 15 days of receiving all information).

- 15 to 30 day comment period depending upon nature of activity.

- Proposal is reviewed by Corps and:

- Public

- Special interest groups

- Local agencies

- State agencies

- Federal agencies

- Corps considers all comments.

- Other Federal agencies consulted, if appropriate.

- District engineer may ask applicant to provide additional information.

- Public hearing held, if needed.

- District engineer makes decision.

- Permit issued or permit denied and applicant advised of reason.

General Permits. There are two types of §404 general permits, regional permits and nationwide permits. In both cases, these types of permits are issued when the proposed activities are minor in scope with minimal projected impacts. General permits reduce the amount of paperwork and time required to start a construction project. Regional permits, which are typically applicable to a certain state or area within a state, are not used for construction activities in wetlands and therefore are not discussed here. Nationwide permits (NWPs) authorize specific types of activity, including construction activities. Permit applications may not be required for activities authorized by a general permit (the rules vary from permit to permit). General permits are valid only if the conditions applicable to the permits are met. If the conditions cannot be met, an individual permit will be required.

Previously, the most widely used NWP for construction activities related to residential and commercial development was NWP 26. NWP 26 was replaced by five new and six modified NWPs, all of which took effect on June 7, 2001. Two of the new NWPs cover work on stormwater-management facilities and two other new NWPs cover activities relating to mining and the construction of recreational facilities. Each of these NWPs is limited in scope and contains numerous conditions that preempt their use except of very specific projects. The recreational-facility nationwide permit (NWP 42) covers only facilities that do not substantially alter the natural landscape, like hiking trails. Small fills at golf courses may be eligible for coverage, but the majority of recreational facilities will not qualify. NWP 39 is the replacement permit covering residential, commercial and institutional real estate development activities. To be eligible for that permit, projects cannot result in the fill of more than § acre of wetlands. A pre-construction notification must be filed with the Corps if the project will result in the fill of more than a specified acreage of wetlands. A list of NWPs can be found here: http://www.spn.usace.army.mil/Missions/Regulatory/RegulatoryOverview/Nationwide.aspx.

Permit Decisions. In deciding whether to grant a permit for a given wetland activity the Corps must follow permitting regulations (CWA Section 404(b)(1)), which are referred to as "sequencing guidelines." Applicants first must establish that impacts to wetlands cannot be avoided. Permit applicants then must demonstrate that reasonable efforts to minimize impacts to wetlands have been made in the design and construction plans. Having taken the first two steps, applicants then must provide a plan for compensation, usually through mitigation, for unavoidable impacts.

On average, individual permit decisions are made within two to three months from receipt of a complete application. In emergencies, decisions can be made in a matter of hours. Applications requiring Environmental Impact Statements (far less than one percent) are averaging about three years to process. The preparation of Environmental Impact Statements is governed by regulations implementing the National Environmental Policy Act (NEPA).

Enforcement. The laws that serve as the basis for the Corps regulatory program contain several enforcement provisions, which provide for criminal, civil, and administrative penalties. The responsibility for implementing enforcement provisions relating to Section 404 is jointly shared by the Corps and EPA. For this reason Army has signed a Section 404 enforcement memorandum of agreement (MOA) with EPA to ensure that the most efficient use is made of available Federal resources. Pursuant to this MOA, the Corps generally assumes responsibility for enforcement actions with the exception of those relating to certain specified violations involving unauthorized activities.

If a legal action is instituted against the person responsible for an unauthorized activity, an application for an after-the-fact permit cannot be accepted until final disposition of all judicial proceedings, including payment of all fees as well as completion of all work ordered by the court.

Presently about 5,100 alleged violations are processed in Corps district offices each year relating to Section 404.

04/20/16 The Grand Prix of Boston race is on a potential collision course with marketing firm HubSpot Inc. over the use of the Boston Convention & Exhibition Center for Labor Day weekend in future years.

Cambridge-based HubSpot has already rented the complex for Labor Day weekend in 2018 and is wrapping up negotiations to return on that weekend for several years after that, bringing with it thousands of attendees and a slew of high-profile speakers.

The IndyCar race organizers, meanwhile, have an agreement with the Massachusetts Convention Center Authority to use the massive South Boston convention complex this Labor Day weekend and have indicated that they would like to return on that weekend in subsequent years. They argue that Labor Day weekend is ideal because many city residents are out of town for the holiday.

The 2.2-mile course circles the convention center, essentially preventing any other big events from taking place there during the race. Race organizers would also use the convention center to support the race.

As of now, there’s no official overlap between the two events. But if organizers for each want to continue using the convention center on Labor Day weekend, there would eventually be a conflict. Last September, HubSpot’s “Inbound" conference drew about 14,000 attendees to the convention center, and that number could grow in future years.

Here’s what the schedule looks like right now: Grand Prix of Boston is booked only for one Labor Day weekend, the one coming up. If the race goes well, organizers hope to return. Next year’s Labor Day is still available, according to a convention center spokesman.

HubSpot then has the place tied up for Labor Day 2018 and is close to signing an agreement to occupy the convention center on Labor Day weekends in 2019, 2021, 2022, and 2023, the convention center spokesman said. (In 2017, the company has chosen another weekend for its conference, as it may also do in 2020.)

A HubSpot spokeswoman offered only a brief comment about the negotiations, saying: “We’re committed to not only growing the event in size but keeping it in Boston in the years to come."

A spokeswoman for Mayor Martin J. Walsh issued a short statement about the potential conflict: “We are focused on this year’s race."

John Casey, president of Grand Prix of Boston, issued a statement saying that the race organizers are “aware of potential conflicts commencing in 2018."

He said the organizers are also aware of construction projects in the neighborhood that could in future years get in the way of the race course by eliminating run-offs — the “overshoot areas" for IndyCar drivers to veer off the main course briefly if they can’t make a turn, to avoid crashing into a wall.

“Grand Prix of Boston has several contingencies in place for 2018," Casey said. “Right now, our focus is on 2016. . . . It is our understanding that 2017, 2019, and 2020 have our names penciled in."

The route, a spokesman said, may need to change in future years to accommodate construction along the existing course.

Bill Wagner, chief executive of race sponsor LogMeIn Inc., said he is less worried about availability on future Labor Day weekends than he is about making sure the race is financially viable. If that’s proven to be true, he said, another date could work fairly easily for 2018 and beyond.

Wagner said he’s optimistic, based on the healthy pace of early ticket sales for this year’s race.

“In the first two years, you know whether or not the economics work for all the parties," Wagner said. “I think if we have a good first inaugural event and follow that up with a good sophomore year, I think you’re off and running." Boston Globe