15 years ago IndyCar, not NASCAR, pioneered the SAFER Barrier

| The IRL broke so many backs, legs and arms back then with their inferior car design, Tony George had to do something and he did. NASCAR likes to take credit for installing the SAFER Barrier at their tracks, but they did not pay to have it designed, IndyCar did |

Today marks an anniversary that Robby McGehee would rather not observe.

But in a way, it’s also a time to celebrate what happened 15 years ago at Indianapolis Motor Speedway because it’s a reminder that the life he enjoys today – with a loving wife, 8-year-old triplets and a successful business career – might have turned out so different.

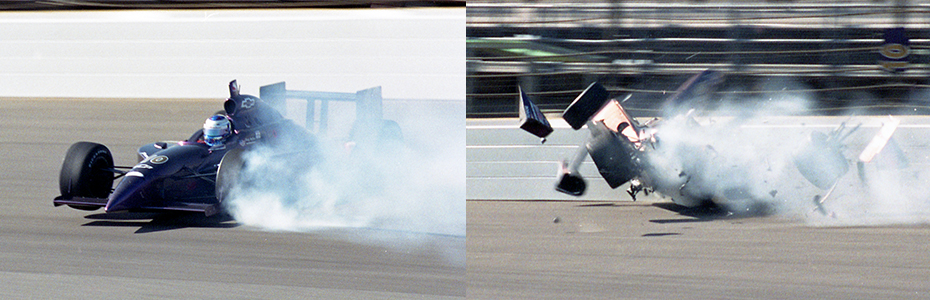

On May 5, 2002, McGehee’s Dallara Indy car spun in Turn 3 and backed into the wall with a thunderous hit. It broke bones in his back and left leg and ended his quest to race in the Indianapolis 500 that year. But McGehee believes the injuries could have been much worse without one of the most significant safety innovations in motorsports history.

That year, IMS became the first racing facility to install the SAFER (Steel And Foam Energy Reduction) Barrier, a “soft wall" system in the four corners of IMS developed as an alternative to the concrete that surrounded the track.

On the opening day of practice, McGehee became the first driver to hit the barrier when the left rear tire lost air and sent the car out of control. Despite his injuries, he’s forever thankful it was there.

“The first memory I have is the sheer pain that I felt immediately after the hit," McGehee said from his office in St. Louis, where he manages Smith McGehee Insurance Solutions. “What makes it beautiful is that I was awake to feel that pain. I went into the wall backwards at 218 mph. Without that 2 feet of give that the barrier provides, I probably wouldn’t have been awake after that. And any time you're not awake, there’s a significant risk of brain injury.

“I still have the picture of the car on fire, on its side, after the initial hit. I look at it every now and then and think, ‘Gosh, I’m happy to be here.’"

Now, every oval where INDYCAR races is protected in all corners and many other vulnerable areas by the SAFER Barrier. In the 15 years since IMS pioneered its use and became the first to install it, the wall has absorbed massive hits.

And, according to the man credited with inventing the barrier, saved several lives.

There has not been a fatality because of wall contact at tracks with the SAFER Barrier, said Dr. Dean Sicking, who led a team of engineers at the University of Nebraska’s Midwest Roadside Safety Facility in developing the barrier. Work began in 1998 with significant involvement and resources from INDYCAR.

“Our goal was to reduce the risk of injury by 50 percent," said Sicking, who now works on similar impact-related research at the University of Alabama-Birmingham. “What we were able to show is that we’ve been able to reduce the actual risk of serious injury by 75 percent."

The barrier seems simple in design – five 8-inch-square, 20-foot-long tubes of 3/16-inch-thick steel, stacked and welded together, then linked to form a continuous barrier. It is backed by bundles of 2-inch-thick, closed-cell polystyrene that comprise a foam cushion about 20 inches between the steel barrier and the original concrete retaining wall. Iowa Speedway, opened in 2006, uses an alternative structure behind the steel and foam instead of a concrete wall, and this year Indianapolis Motor Speedway installed a similar SAFER Barrier inside the track in Turn 3 to replace a steel guard rail.

The SAFER Barrier’s function is more complex than simply cushioning the energy of a car.

It’s the combination of steel and foam, and the shape and construction of those components, that not only softens but also changes the timing of the impact forces compared with a crash into an unforgiving concrete wall. As a result, G-forces are less severe on the driver.

Sicking says there actually are two impacts that the car absorbs, but the driver only feels the first because of the barrier’s design.

“The mass of the wall is configured such is that it takes about half of the velocity of the vehicle out in that first impact," Sicking said. “Then the wall will coast and is crushing foam blocks. At that point, the driver is coming out of his seat, stretching his belts. Then, as his belts become fully extended, they start pulling him backwards."

When the steel barrier compresses the foam to its maximum, the G-forces on the car increase again, Sicking said. But the driver never feels those forces because he is moving back toward the seat.

“When that second event occurs, the peak G-forces are about 85 percent of what you get with a normal concrete impact," he said. “We separate the impacts into two different events and we make it so the second impact isn’t felt by the driver."

Since the SAFER Barrier was installed, most INDYCAR crashes have recorded G-forces at between 60 and 65 Gs, said Jeff Horton, INDYCAR’s director of engineering and safety.

“The biggest thing I remember seeing when we went to the SAFER Barrier was the step change in lowering the G-forces," Horton said. “I always use the (Indianapolis Motor) Speedway as a reference because that’s where we hit the hardest. We remember the concrete hits being 100-plus Gs on the cars."

What’s the highest survivable G-force on a human body?

“Nobody knows," said Dr. Terry Trammell, INDYCAR safety consultant and longtime medical director for open-wheel racing. “But anything in the 70s (on the car) gets our attention."

The SAFER Barrier, in combination with head and neck restraints, plus energy-absorbing material and safety mechanisms to the car that Horton and Trammell helped develop, undoubtedly gives the driver a greater chance of reduced injury in a wall contact. If the driver gets hurt at all.

“You can see on the black box tracing that the first thing that happens is that the car gets used up, then it starts to move the foam in the SAFER Barrier," Trammell said. “It’s not a soft wall, but it’s softer than concrete."

Sicking and his team learned a lot from McGehee’s crash in 2002, which led to development of a second version of the SAFER Barrier that was introduced late in 2003.

Tests before the first barrier was produced didn't factor that the car’s tires might deflate before hitting the wall, resulting in contact lower on the barrier than Sicking’s team had anticipated. The left rear tire on McGehee’s car lost air pressure to start the spin and other tires went flat before he hit the wall, Sicking said.

“We had prepared the barrier to be hit by the back end of the Indy car, but we thought the tires would still be aired up," he said. “When we went back and looked at all the crashes, most of the time the tires were aired out before they got to the wall."

The original SAFER Barrier had a taller bottom steel tube. When McGehee’s car backed into it lower on the wall than expected, the gearbox punctured the bottom tube. Version 2 features five steel tubes of equal dimension, all 8 inches tall, plus foam blocks that are shaped differently than the original barrier. Sicking says the barrier is designed so welds between the steel tubes will break under excessive G-forces, providing more give to the wall.

Version 2 remains the standard at speedways today.

“The barrier has proven itself," Horton said. “In my mind there have been two significant step changes in safety. One is the SAFER Barrier and the other is the HANS (head and neck restraint). We consider those step changes because you’re talking about a 40-percent reduction in Gs at a place like Indy."

James Hinchcliffe’s crash into the Turn 3 wall in 2015 at Indianapolis was the hardest Indy car hit into the SAFER Barrier – 125 Gs – that most officials can recall. Hinchcliffe suffered a critical injury when a suspension piece came through the tub and pierced his hip.

Horton said INDYCAR is involved in a joint venture with the University of Nebraska and NASCAR in looking at ways to ensure the SAFER Barrier remains as effective now as when it was installed years ago.

“There hasn’t been much talk about (new) design," Horton said. “The main topics are about the longevity of the foam and all of that. Now that the walls have aged, we are making sure they don’t lose their performance based on that. Ultimately, the right way to do it is that you’ll see tracks lined inside and outside, because it’s amazing where cars can get."

As that process develops, the SAFER Barrier will continue to cushion hard hits, lessen injuries and save lives. McGehee, the first driver to crash into the barrier, remains thankful 15 years later.

“I’d love to be remembered for 1999 and winning the Indy 500 Rookie of the Year more so than this," he said. “But 100 years from now the only thing people will know my name from is being the first to test this new technology that will probably still be in place. I feel blessed to have lived and raced and done what I got to do. I never won at that level but I came close several times. But I’m walking around, I’ve got 8-year-old triplets and a great wife.

“Any time you can drive a car at that kind of speed, hit a wall, get out and walk away, it’s amazing. As a driver, anything that works on our behalf to keep us alive in a bad situation will help us sleep a little better at night. This is an inherently dangerous sport. The love and passion and drive of the sport always over-rides that, but this helps you feel better about it." Kirby Arnold/IndyCar.com