Why Alonso can win with Honda at Indy but not in F1

|

| Honda underestimated F1's silly hybrid technology. In the future cars will be 100% electric and all that silly hybrid technology F1 has on its cars goes away sans the kinetic energy recovery system when a car brakes. But manufacturers already have that. IndyCar has the right formula |

If somebody who only follows Formula One or IndyCar turned on one of the other series’ races, they probably would be shocked to see Honda running at the opposite end of the field. But if you look at the Japanese manufacturer’s current situation in each series, the dichotomy becomes a bit more understandable.

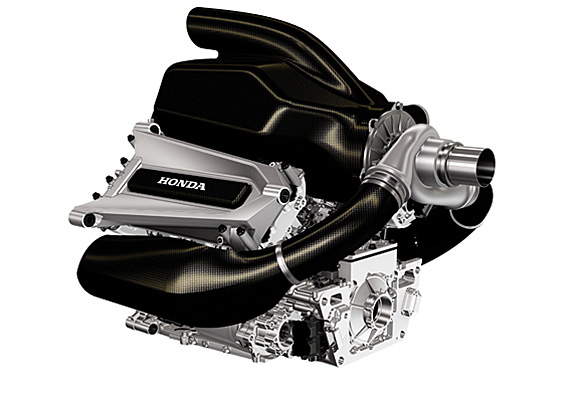

Although IndyCar and F1 are two of the top single-seater series in the world, the racers used in each are very different, with F1 cars pushing the envelope more in terms of technology. Both categories use V-6 engines that are turbocharged — one turbo in F1 and two in IndyCar — though that’s about where the similarities end. In addition to forced induction, F1’s internal combustion engines have their power outputs boosted by complex hybrid systems, which have proven to be Honda’s undoing.

When Honda returned to F1 in 2015, the sport was in its second year of the hybrid era, so it encountered many of the growing pains that other manufacturers — save Mercedes — experienced in 2014. Its power unit also was packaged such that it struggled with cooling, and therefore couldn’t deploy all of its electric power down the straights. To add to its problems, the errors it made in year one of the revived McLaren-Honda partnership were only compounded by F1’s engine token system, which limited development.

However, with an entirely redesigned power unit, and no more token system, Honda’s problems have actually gotten worse in 2017. The reliability for which Honda’s road cars are known is nowhere to be found, and even when McLaren’s cars can turn a few laps, they’re at an even bigger power disadvantage than before.

That’s in stark contrast to its current-generation IndyCar engines, which have won three of the last five Indianapolis 500s, and power some of the most competitive teams in the series, such as Andretti Autosport and Chip Ganassi Racing.

Although Honda’s unfamiliarity with F1’s hybrid powertrains is the main reason it has struggled, it’s not the only one. Its engineers also severely underestimated how foreign the technology truly was to them, and overestimated their abilities, likely assuming the knowledge it attained in American open wheel racing would be more directly applicable. The problem with that line of thinking is that it doesn’t take into account all of the groundwork Honda already had laid for its success in IndyCar.

It had been in the sport for a while before the twin-turbo V-6s were introduced in 2012, giving it invaluable insight when designing its current engine. In F1, however, it essentially was shooting in the dark when it designed its 2015-spec power unit, as it had last raced in F1 in 2008.

Honda’s abrupt exit from F1 meant it didn’t even have experience with the kinetic energy recovery system that was introduced in 2009 as a precursor to the current fully integrated hybrids. When you compare that to the preparation other teams put into their hybrid units, it’s clear why Honda is struggling.

Mercedes, which had the dominant power unit from 2014 through 2016, began planning its design when it returned as a full works team in 2010. By signing Sauber F1 Team as its second customer team starting in 2018, Honda has given itself a chance to claw its way out of this abyss, but it still has a long road to recovery. In the meantime, Fernando Alonso’s Indy 500 entry will remind F1 fans that Honda still knows how to make an engine that’s competitive on a power-dependent circuit. Pat McAssey/NESN