The Underdog Upset

|

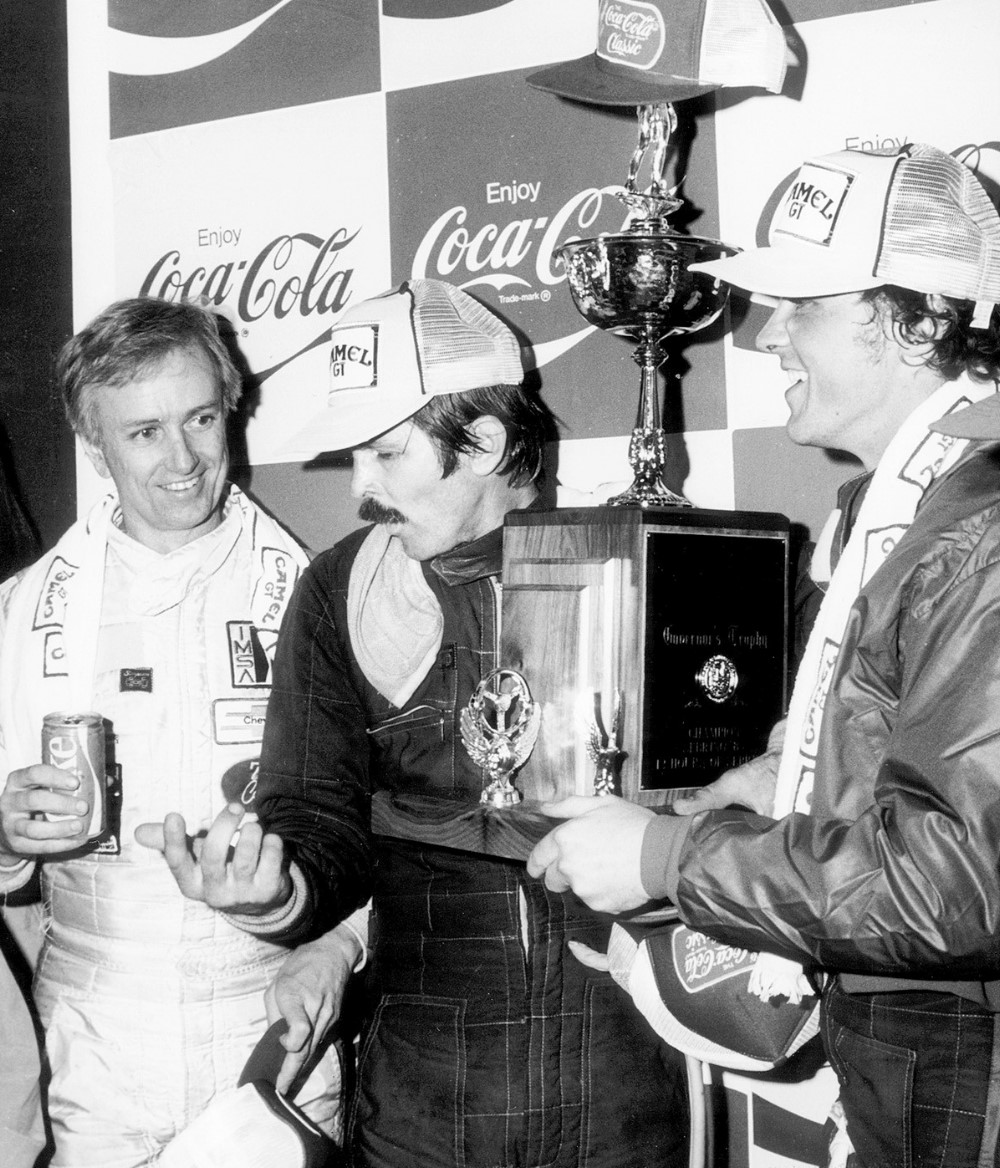

| Wayne Baker, Jim Mullen and Kees Nierop pulled off an upset win at Sebring in 1983 |

Americans love underdogs but hate losers. And we really love upsets because they turn reality inside out and generally make the mighty look weak.

So when anyone demands a prediction, I try to hide because I always remember some races that didn’t quite go the way the experts reckoned: the 1954 Sebring 12 Hours, 1955 Monaco Grand Prix, the start of the 1958 Race of Two Worlds at Monza (not the whole race, but the start sure was a great moment for sports car types).

And then … there was the 1983 12 Hours of Sebring.

The grid that year was a menagerie of cars (including a GTU Ford Pinto!) and classes. Eighty-four entries… the number whispers “weirdness", with “upset" added in parentheses.

This was the year of Sebring’s “amputation." In 1983 nearly a half-mile of the old 5.2-mile circuit’s airport runways were bypassed by new pavement. The FAA finally was happy, and Sebring remained the longest road racing circuit in America – and the one with the worst temper and temperament. Stand by for sunset, weirdness fans.

Three decades earlier, one would have been forgiven for picking Stirling Moss to win the 1954 Sebring race simply because he was Stirling Moss, even though he was driving a puny 1.5 liter OSCA during his first race in America.

But no one picked Wayne Baker’s No. 9 Porsche 934 to win the 1983 12 Hours. No matter. Wayne, ace vintage and historic racer Jim Mullen and Kees Nierop did just that in the well-used – and 1981 Daytona 24 Hours-winning – 935 that Wayne converted to 934 specs and then back again later.

They started 14th – outside row seven and right in front of the No. 7 upset contender Mazda RX-7 of Pete Halsmer and Rick Knoop. The yellow “school bus" 934 just plugged around trying to stay within sight of the GTO podium. When the third “hourlies" were published, old No. 9 had eased into the overall top 10. The rest of the field – including a few new GTP cars – suffered bouts of chemical and mechanical illnesses, plus the typical wicked Sebring fates that make us love the race. By the end of the seventh hour, the school bus was being widely ignored – despite its top-10 performance – as Halsmer and “the Knoopster" had the amazing Racing Beat Mazda up to second overall. And it wasn’t even dark yet.

If you were there 30 years ago, you might remember an odd full-course caution period to permit a fuel truck to cross the course. With 84 entries, the paddock fuel depot was running low. The truck with the replacement fuel couldn’t ascend the bridge to the paddock, hence the caution.

Sebring reveals its true self after sunset, of course. When Bob Akin’s leading Cokemobile 935 pitted with a juicy two-lap lead, it wouldn’t restart. He placed the blame on water in the (new, fresh) fuel. The usually gentlemanly Akin was furious and said so in very plain language on national television.

But it was mild stuff coming only a month after a very cranky Bob Wollek had said that word-that-can’t-be-said on television, out loud and live on TBS during the Rolex 24 at Daytona. You may remember the circumstance: Preston Henn put A.J. Foyt in the Daytona-leading Swap Shop 935 to relieve Wollek. Foyt had never driven a 935. It was raining. Wollek practically came unglued. Then he said that word, live on TV. After that, Akin’s stern comments regarding his Sebring gasoline provider seemed measured and demure.

With the Akin Cokemobile stationary, the Racing Beat GTO Mazda RX-7 went to the top and stayed there for more than two hours. With not much more than an hour remaining, the heroic RX-7 stopped with brake and suspension problems. The Milt Minter/Skeeter McKitterick Grid GTP (they only made two Grids, so it’s no big deal if you never heard of the Cosworth-powered British GTP) went in front… but not for long. Handling trouble compelled them to surrender the lead to the Hurley Haywood/Al Holbert Bayside 935. Haywood and Holbert led Sebring: sanity seemed restored. Then the lights went out on their No. 86.

|

| The winning No. 9 Porsche |

Deep in the eleventh hour, the “school bus" (as many now called Wayne’s stout yellow No. 9 935/934 GTO Porsche) eased into the lead. But it was low on fuel and its handling had decayed. The 31st annual 12 Hours of Sebring was about to become the biggest upset since 1954 (if you count any race won by Stirling Moss an upset).

Wayne’s crew didn’t tell him he was leading overall. When they directed him to Victory Lane and the flashbulbs started popping, he had a few moments of confusion. Hardly the first of the bizarre race day.

It was the slowest Sebring since 1963, but a speed record for the new 4.75-mile airport course. There were eight lead changes among 23 cars across three classes – another Sebring record. It was the seventh time Sebring produced a 1-2-3 finish for Porsche, and it wouldn’t be the last. A year later the Sebring winner was an undercard 935 that was exhumed from a museum and rented for the 12 Hours. In 1985, Wollek decided that Foyt was just the sort of plain-speaking, hard-ass co-driver he’d been looking for, and the pair led yet another Porsche 1-2-3 at Sebring – the first for Porsche’s brilliant 962.

But in three decades and through three sanctioning bodies – and I forget how many circuit modifications – it never got as weird as the night of March 19, 1983.

Charles Dressing is one of sports car racing’s foremost historians and is a walking, talking encyclopedia on the sport. Part of the ALMS broadcast and production crew, his blog appears every other Wednesday.